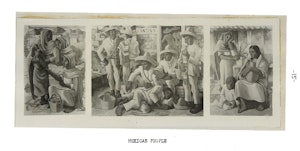

Edmund Daniel Kinzinger

Mexican People

c.1942

Page 19, 'A Series of Oil Paintings' a dissertation by Edmund D. Kinzinger, University of Iowa, U.S.A., 1942

A SERIES OF OIL PAINTINGS

by

Edmund Daniel Kinzinger

A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the department of Art in the Graduate College of the University of Iowa

July, 1942

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I wish to express my gratitude for the advice, criticism, and encouragement received from the members of my committee, Dr. Lester D. Longman, Mr. Alden Megrew, and Mr. Philip Guston.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Acknowledgments … ii

I. Content … 1

II. Scheme of Composition … 2

III. Form … 4

IV. Color … 8

V. Application … 11

Footnotes … 14

Photographs … 15

MEXICAN PEOPLE

I. Content

The series of three oil paintings, MEXICAN PEOPLE, is not intended only to depict a slice of Mexican life at a particular moment, but is also an attempt to express the philosophy of the Mexican Indian. I do not know of any border between two countries where two different ways of life contrast to such an extent as between the United States and Mexico. The United States is highly civilized; the people are on the hunt for money and most farmers are inclined to be farm industrialists, losing the love of earth, the admiration for nature’s beauty, and the enjoyment of the products of art. Mexico is still primitive and religious; the native is part of the earth which provides him with his daily needs. He expresses his love of nature by beautifying with designs of his own invention every kind of implement he makes and uses in his dally life. So is a true part of the earth to which even his skin color Is akin. Genuinely humble and yet proud in bearing, he wears his simple clothes with the grace and dignity of a grand seigneur. An inexpressible happiness like a melancholy dream seems to possess the Mexican; and the taste, the restlessness and the disillusionment of our modern age are unknown to him.

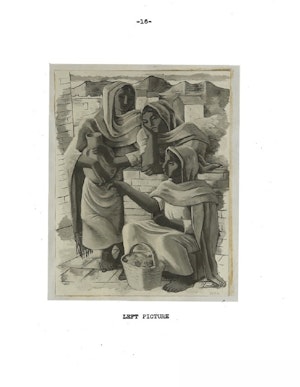

The center piece of MEXICAN PEOPLE represents a group of young men assembled around the Cantina where, in laconic conversation, they discuss their problems. Church and market are over and after a visit and a drink they will return to their hamlets. The panel at the left represents women resting on their return from the public fountain or the market; while the right panel depicts a mother with her two children before the porch of their house, which, typical of villages of a high altitude, represents a mixture of native and Spanish colonial style.

I spent six months In Mexico mostly In Taxco where the studies for all three paintings were made. I was deeply impressed by the natives and their organic relationship with surrounding nature. The paintings are not meant to be a triptych in the strict sense, but it was my intention to bind them together by certain construction lines which would lead the eye from one painting to the other. Moreover, a similarity of gestures and the repetition of forms and objects provide an encompassing unity when the paintings are hung next to one another and in the proper order.

II. Scheme of composition

All three paintings have a proportion 3 to 4, which gives a diagonal of 5. This proportion has been preferred by artists since the earliest times. Half of this rectangle, the triangle with sides proportioned 3 to 4 to 5, was described by Plato, the Greek philosopher, as being the most beautiful of all shapes. Many Romanesque churches and other buildings of different periods are derived from constructions based on a proportion of this triangle. Today, we even find the proportion 3 to 4 in the shape of our typewriting paper as well as in charcoal paper and many other items of daily use. The introduction of the golden-mean proportion, (short side to long side as long side to the whole) gives this rectangle an interesting interplay of arithmetic and geometric means.

It is not my opinion that the artist shouId stick to these first considerations under all circumstances because, in the process of development, color planes change their original size through the introduction of light and dark and through the various intensities and qualities of the colors which the artist applies. Feeling should always be the first guide, but it is astonishing to the student of composition how the greatest masters of composition, Raphael, Tintoretto and especially El Greco used their first construction lines without altering them in the process of development. Among modern masters, the Neo-Impressionist, Seurat, and still more recently the French Cubist, Juan Gris, could be mentioned as giving serious attention to the construction of the picture plane. Since Egyptian times, proportions and their logical development have always played the most important role in architecture. Modern architecture depends basically on simple proportion, a consideration which was stimulated by the Stijl group of Dutch painters (Mondrian, VanDoesburg). It is up to the artist to put life and the spirit of invention into his construction. Juan Gris said in a lecture delivered in 1924 at the Sorbonne in Paris, "All architecture Is a construction, but not every construction is architectural.” For the painter, the limitations of a construction form a certain restriction in options, giving him a foundation for his work. A Chinese artist of the T’ang period said with great truth: “Limitations are the artist’s best friend.” All great art is disciplined.

III. Form

The content and the compositional scheme of a picture are only the background of the painter's work. The solution of the problems of form and color, to express volume and space in a unified and rhythmical depth-movement, is the major design problem. This should be done without disturbing the two-dimensionality of the picture plane; nothing should fall out or make a hole in the canvas. It is the task of the artist to find the equation in which the naturalistic feeling of depth, including the rendition of the volumes, is transformed into a formal and expressive order. The parts have to be arranged around certain points centrals, as Cezanne called them, that a perfect, though asymmetrical balance is achieved, in which the feeling of depth and volume is absorbed by rhythmical movement, showing the parts in an inner relationship. Cheney in Expressionism in Art1 calls this the plastic orchestration of a painting. It is possible to explain this scientifically. We see primarily only in two-dimensional color spots, which the mind combines through earlier experiences of all the senses into volumes and their relation in space. Goethe says that with each attentive look we build a theory, which leads to the understanding of the impression. A child has to learn to see; he has first no feeling for distance, tries to grasp a church tower, falls over chairs, and bumps into tables before he learns to calculate. He opens and closes his hand, getting nearer and nearer to the desired object until he touches and can grasp it. Three-dimensional form is thus a mental construction. Appearance differs for every one according to the reliability of the eye, the degree of concentration, the level of experience, the power of thinking, and the circumference of knowledge. If any of those considerations change, seeing, especially artistic seeing, changes too.

The mystery of pictorial creation is based on the relation of two- and three-dimensional seeing. Nature is really three-dimensional, though its appearance is two-dimensional. It is only through understanding that appearance becomes three-dimensional. We differentiate, therefore, not only between nature and appearance, but also between appearance and the effect of appearance. Sometimes, in modern art especially, appearance is something entirely different from the effect that comes from it. It becomes clear, therefore, why various art directions of our times use such distorted forms; the painter has become thoroughly conscious of his freedom of interpretation.

Melvin M. Rader in A Modern Book of Esthetics2 contends in the introduction: “The effect of naturalistic distance is not of the slightest artistic importance unless it functions in terms of value expression. It was what Oswald Spengler calls it, the creation of a spiritual space, wide and eternal, which responds to the imperious need of Western man for a symbol of distance and the infinite. When, with Bouguereau, space becomes only a trick of copying we do not have a depth-experience that is significant or esthetic; when with Cezanne space is a harmony of deep, solid, and subtly related masses, the distance-thrust yields an inner imaginative order—an expression of values and therefore the very stuff of art. We discovered, among other things, that most of the great art of the world has been unrealistic; or rather, the realism of art was spiritual in character as in the ideal of Cezanne who said: ‘I have not tried to reproduce nature, I have represented it.’”

This conception of space can be clarified by the following quotation from Henry Kahnweiler's book, Der Weg zum Kubismus3: “A distinct final plane enters the pictures of Braque and Picasso from 1908 which limits the vision. Instead of an illusional horizon against which the vision looses itself, a chain of mountains in a landscape or a wall in still-life or figure composition closes the painted three-dimensional space. We have seen the same limitation of picture space in Cezanne's work. Instead of starting from a foreground and suggesting an illusionary depth through the means of perspective, the new painter calculates from a represented background. From this background, he works for ward [sic] in a kind of form scheme in which each object is represented in relation to the background and the other volumes. This new method allows the painter to represent the objects in relation to their placement in space, instead of imitating them through illusional means. These representations have a certain resemblance to geometry, which is quite understandable since both aim to represent the third-dimensional volume on a two-dimensional plane. This new language has given an unknown freedom to the artist. No object has been created by man whose lines are not geometrical as a cube, sphere, or cylinder. Nature seldom has these regular forms, but they are deeply rooted in man's mind. Without them there would be no definite feeling for the three-dimensional world." (Translated from German by Edmund Kinzinger.)

In order to clarify my relation to a school, I should call myself a follower of the intellectual principles of Cubism. I have been deeply impressed by the cubist pictures of the French school from the time I first saw them in 1910 and have worked in that direction ever since. Being of a rather romantic nature, however, and very much bound to direct impressions, my development reveals many conflicts. Thus both in form and content, my thesis pictures represent an effort at a reconciliation of the very basic clash between architectonic design and emotional expression.

It is in the character of our age that artists change their style from time to time, inclining more to abstract form at one moment and leaning more toward representation at another. In all epochs previous to the late 19th century, the understanding of other periods was restricted by a lack of historical knowledge and easy communication. Therefore the isolated artist had to rely largely on his local tradition. Today, we have a thorough knowledge not only of the contemporary art of all countries, but also of nearly all the past of the human race. The resulting influences on intelligent and informed artists are manifold, and change of style, as long as it is consistent with the artist’s personality, is rather a sign of spiritual flexibility than a lack of conviction, as it is sometimes interpreted by unimaginative observers. Only through doubt and experiment are invention and progress possible. My graduate studies in the history and criticism of art, and my effort to reach a new level of esthetic expression in the painting of my thesis, thus represent evidence of the searching and genuinely creative attitude engendered by the Ph.D. program I have followed.

IV. Color

The solution of the color problem also presents a great challenge to the painter. He likes to give to his colors a relationship to nature and at the same time to develop an expressive pattern. Thus, since a compromise must be made, the modern artist simplifies and transforms the realistic color appearance to arrive at his personal solution of the impression and to give to his picture the quality of surface that may be called color architecture. Color harmony, if I may use this doubtful expression, can only be developed in relation to the fundamental characteristics of color, which are hue, value, and intensity. The great variety of theories on color harmony which we find in books may be satisfactory for the design of wall paper, but are unsatisfactory for painting. The artist tries in relation to his aim to express unity and variety at the same time.

Unity can be achieved:

By using monochromatic colors, that is colors which are derived from the same hue. In this case, contrasts of values and intensities to satisfy the desire for variety will necessarily be introduced. The artist may also add neutral colors, which through simultaneous contrast will be influenced to take the complementary character of the reflected light. Without disturbing the monochromatic scheme, he may also add to his original hue some of the neighboring colors, or he may strengthen the simultaneous influence of the neutrals by giving them a bluish or reddish character (as the case may be) of low intensity. We see such color combinations in Picasso's blue and rose periods as well as in his grey-red nudes. The work of Rembrandt and other old masters may also be listed as examples.

By colors of the same value, and ordinarily of the same intensity, as seen in the Impressionistic period. Variety is given by the use of many hues.

By colors of the same intensity, often pure colors as in Van Gogh and Gauguin, in the German Expressionists and the Fauves. Variety enters here through the difference in the value of pure colors.

By analogous colors, i.e. colors which are near to each other in the color circle. Not more than three or four colors should be chosen lest the contrast become too great. Variety is introduced here by value and intensity. One color being dominant, there is a resemblance to number 1; this method has been used in all periods of art.

Variety can be achieved:

By contrasting colors, one color pair being mostly dominant. Unity enters through value or intensity. Examples are the work of Matisse and much Oriental art.

By contrast of light and dark (value). Unity is achieved through nearly monochrome colors. Ribera, Rembrandt, and the early cubists used this method almost exclusively.

The beauty of contrasting colors in any color scheme does not come from the simple contrast of the colors but from variety, for example varied reds against a variety of blues. This tremolo of color (to use a tonal expression) very often gives an abstract and musical quality to a picture.

I am certainly aware that no definite rule of color combination can exist for painting, but the above-suggested combinations are fundamental ones used in my work. It is not the colors themselves but the proportions and relations of the color spots, which make the most difficult problem.

V. Application to my thesis of the means of expression discussed in this description

In the three oil paintings MEXICAN PEOPLE, I have used a color scheme derived from the contrasting colors of red and yellow-browns against blues and greens. The harmony of the dark skinned people with the color of the earth was the reason for this choice. The formal means are derived from Cubism: plastic organization in three dimensions, freedom of form from descriptive realism, and restriction of literary connotation. The design values are moderated and balanced, however, by an attempt to stay as near to representational form as possible without disturbing the plastic organization.

My style seems to me to have greater opportunities today than naturalistic art or art which deals exclusively with abstract forms. The abstract artist refrains from giving any personal observation concerning his surroundings and often neglects the fascinating problem of rendering the three-dimensional world on the two-dimensional canvas, which is the very essence of Cezanne’s work as well as the spiritual efforts of the cubists. The only thing the abstract artist can achieve is rhythmical pattern with the expression of mood, the very stuff of which music is composed. Walter Pater's observation that "All art inclines to the purity of music" is true, but abstract beauty alone, in my opinion, is not sufficient for painting, for the painter, in contrast to the musician (whose medium is by nature abstract), can never reach the goal of pure tonal orchestration. The possibilities of music, which can only be appreciated in time, are far more numerous than the possibilities of abstract painting, in which the painter is unfortunately bound to static form. The artist has to seek significant human content through form, in addition to exploiting abstract pattern, in order to make his work comparable in importance to a great symphony. For this reason, many abstract painters turn their attention to industrial design and architecture where, because of the additional dimension of useful function, abstract means are of more importance. I painted in an abstract manner from 1917 to 1920, but I soon missed the inspiring reactions to natural impressions and turned to a more representational style.

The artist who paints too naturalistically, on the other hand, overlaps the domain of photography and the cinema, which through their technical nature as reproductive arts, and the latter as art in time, are far superior to painting in recording the visual aspects of nature. Furthermore, too much concentration on conceptional ideas overlaps the domain of literature, which is better suited to ideational purposes.

Therefore a reconciliation of the demands of representation and design to their mutual advantage has been the task for the painter of many periods and is the first principle of numerous progressive painters today. In the three paintings, MEXICAN PEOPLE, I have attempted such a solution.

FOOTNOTES:

1. Sheldon Cheney, EXPRESSIONISM IN ART, Liverright Publishing Corporation, 1934. Mr. Cheney collected many ideas for his book through contact with earlier students of the School of Fine Arts of Hans Hofmann, Munich, which I conducted as director from 1930-33.

2. Melvin M. Rader, Assistant Professor of Philosophy, University of Washington, A MODERN BOOK OF ESTHETICS, Henry Holt and Company, 1935.

3. Robert Henry (Pseudonym for Henry Kahnweiler), DER WEG ZUM KUBISMUS, Delphin Verlag Munich, 1918. Mr. Henry Kahnweiler was the art dealer of the first Cubists.

Cover and Copyright pages, 'A Series of Oil Paintings' a dissertation by Edmund D. Kinzinger, University of Iowa, U.S.A., 1942

Acknowledgment and Table of Contents pages, 'A Series of Oil Paintings' a dissertation by Edmund D. Kinzinger, University of Iowa, U.S.A., 1942

Pages 1-2, 'A Series of Oil Paintings' a dissertation by Edmund D. Kinzinger, University of Iowa, U.S.A., 1942

Pages 3-4, 'A Series of Oil Paintings' a dissertation by Edmund D. Kinzinger, University of Iowa, U.S.A., 1942

Pages 5-6, 'A Series of Oil Paintings' a dissertation by Edmund D. Kinzinger, University of Iowa, U.S.A., 1942

Pages 7-8, 'A Series of Oil Paintings' a dissertation by Edmund D. Kinzinger, University of Iowa, U.S.A., 1942

Pages 9-10, 'A Series of Oil Paintings' a dissertation by Edmund D. Kinzinger, University of Iowa, U.S.A., 1942

Pages 11-12, 'A Series of Oil Paintings' a dissertation by Edmund D. Kinzinger, University of Iowa, U.S.A., 1942

Pages 13-14, 'A Series of Oil Paintings' a dissertation by Edmund D. Kinzinger, University of Iowa, U.S.A., 1942

Pages 15-16, 'A Series of Oil Paintings' a dissertation by Edmund D. Kinzinger, University of Iowa, U.S.A., 1942

Pages 17-18, 'A Series of Oil Paintings' a dissertation by Edmund D. Kinzinger, University of Iowa, U.S.A., 1942

Edmund D. Kinzinger, Study for Cantina Triptych, c. 1940, mixed media, unsigned, 180 x 240mm

Photo: Courtesy https://www.vintagetexaspaintings.com/texas-art/1276-edmund-daniel-kinzinger-unsigned-study-for-cantina-triptych-mixed

Reproduced with the kind permission of Nancy Kinzinger

Edmund D. Kinzinger, Study for Cantina Triptych, c. 1940, mixed media

Photo: Courtesy https://www.vintagetexaspaintings.com/texas-art/1276-edmund-daniel-kinzinger-unsigned-study-for-cantina-triptych-mixed

Reproduced with the kind permission of Nancy Kinzinger