Cover and page 1, Edmund D. Kinzinger: The Early Years 1913-1935 exhibition catalogue, The Gallery, Hughes-Trigg Student Center, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Texas, U.S.A., 1992

It is the privilege of The Gallery at Southern Methodist University to present the first major exhibition of the early drawings, collages and paintings of Edmund D. Kinzinger to be shown in the United States. The exhibition focuses on more than sixty works produced by Kinzinger while still in Germany before his emigration to America just before the outbreak of the Second World War.

Rarely do we have the opportunity to view a body of work that so closely reflects the changing identity of an era that occurred in Europe at the beginning of the 20th century. It is important historically to note that the social concerns about the dehumanization of society by modern technology would not occupy most German artists until around 1930. The prevailing interest for artists at the turn of the century was in developing a wholly new visual vocabulary, not on continuing the old traditions or even re-inventing them. The abstract or nearly abstract images seen in Kinzinger's early work and that of his contemporaries have as their precursors work begun in the 1890s by a variety of European artists such as Wassily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich and Piet Mondrian. Early in the 1912 Kandinsky s publication On the Spiritual in Art brought together for the first time the mixed equation of expressionism, mysticism and abstraction. The writing was widely read in Germany and the subject of much debate and lively discussion by artists, critics and the public at that time.

Edmund Daniel Kinzinger was born at the end of the 19th century on December 31, 1888 in Pforzheim, Germany. His father was the owner of a jewelry store in Pforzheim and was considered a solid member of the German upper middle class. We know that even as a young boy Kinzinger painted and soon after high-school he enrolled at the Stuttgart Academy for the Arts.

While at the Stuttgart Academy Kinzinger met and studied with the Swiss painter, Adolf Hölzel from about 1912 to 1914. The very earliest work in this exhibition dates from this period. Those early years of the 20th century formed a bridge between Post-Impressionism and pure abstraction. Symbolism, the mystical wing of the Post Impressionist generation, was a strong presence in Germany during this period of transition. Another of Hölzel's students at the time was the painter Johaness Itten who was to become a major early instructor in the Bauhaus group founded in 1919 by Walter Gropius. Itten was greatly influenced by mystical practices and later developed one of the most distinctive artistic personas of the period. The role that Itten assumed included wearing monks robes and having a cleanly shaven head.

The undeniable abstract power of perception found in Kinzinger's early works is directly linked to the new emphasis on the spiritual taking place in Europe in the late 19th and very early 20th century. As European artists sought to unite abstraction with mystical concepts to create meaningful images they looked to the study of Theosophy for a guide to the expression of ideas that had previously seemed inexpressible. Theosophy, a philosophy based on mystical insight into the nature of God, began to be linked with a search for a way to transform society and with a reaction against materialism and industrialism dominating late 19th century Germany. For many artists of this period, Kinzinger included, the path to this transformation led away from representational art and towards abstraction. For a brief period this move fell within a particularly German tradition of what might be referred to as visionary representational art.

Kinzinger served as an artillery officer in the German army from 1914 to 1918, serving on the front for most of those years, and was wounded twice. In the years since 1913 Kinzinger had begun to synthesize the many artistic influences found in the varying aspects of his surroundings and his own personal experiences. There seems to be little doubt that he had seen the harsher realities of his time and began to make an art that reflected the redeemable.

During World War One the expressionist movement in Germany began to absorb influence from other modernist styles, mainly French cubism and Italian futurism. Kinzinger's work during this period is a synthesis of all these styles but a synthesis still imbued with his own particular sense of the mystery of life. The work becomes a metaphor for the inherent beauty in the passage of time, the sense that everything has its undeniable moment in time and then passes (or does it?) in the German mind. The mystical, moody quality of the work testifies to the spiritual connections that fuelled Kinzinger's search for transcendence through art.

In 1919 Kinzinger along with Oscar Schlemmer, Willi Baumeister, Oscar Graf, Hans Spiegel and Albert Mueller formed an artist group called Üecht-Gruppe. The Üecht-Gruppe met regularly to talk and exchange new ideas but seemingly shared no central style or theory. In fact, the members had such different styles that their work is still very difficult to even recognize or identify as a group. During the next few years Kinzinger met Hans Hofmann and became friends with Picasso in Spain. He also expressed much interest in, and greatly admired, the sculpture of the Italian Futurist Alexander Archipenko and had in fact acquired four of his works.

After World War One the release of energies and feelings into an art imbued with deep mystical and spiritual connotations began to be criticized as being decorative and without meaning. The liberating moment in which German expressionism flourished seemed gone after the war. Artists searching to transform society became more enamored with technology and less with the mystical needs that had fostered the growth of German expressionism.

Kinzinger was not immune to these societal changes, and his work now began to take on a more analytical cubist look in which surface and spatial movements create the critical balance between content and form. His work closely resembles that of his contemporaries except for the mystical moodiness that seems to lay just under the surface of even the most non-objective works from this period. Their poetic mood springs less from his use of saturated, luminous colors and evocative forms and more from some undeniable power of perception drawn from his sense of the deep mystery of life. This mystic moodiness has its roots in personal inspirations. In this, Kinzinger drew upon German landscape painting traditions that existed before 1900.

The rise of Nazism in Germany forced Kinzinger to leave his country in 1934. Eventually most of the intellectual community of Germany would be forced to flee. He established his own school in Paris, the Ecole de L’ Epoque and had a one person show at Gallery Pierre in Paris. During this period he made contact with many of the Cubist artists working in France. The work surveyed in this exhibition covers only the years between 1913 and his final departure from Europe to the United States in 1935.

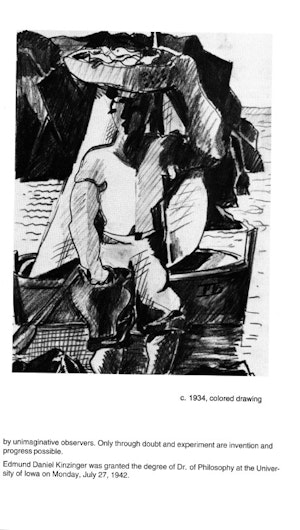

In the United States Kinzinger found a position as Chairman of the Art Department at Baylor University in Waco, Texas and remained there until 1950. It can not be overstated that new surroundings for an artist can often be difficult. Kinzinger had spent a summer in Taxco, Mexico, in 1930, and soon after began to incorporate Mexican subject matter and motifs into his work. In 1942 he received the first Doctor of Arts degree granted by The University of Iowa. There he developed his interest in Mexican imagery for his thesis which consisted of a group of paintings. His transition to America seemed blunted, however, by the new surroundings, personal problems, failed marriage and depression. The move away from European thought and influences proved a hard one to make.

It is interesting to note that this artist, who was so much a part of the search for transcendence through art that occurred in Germany in the first part of the 20th century, would, in 1944, purchase land and begin to spend summers in Taos, New Mexico, surely one of the most transcendental places in North America. Only six years before his arrival, a fusion of the spiritual and abstract had occurred in Taos with The Transcendental Painting Group formed by Raymond Johnson and Emil Bisttram. The work of these New Mexican transcendentalists is strikingly similar to the mystical and spiritual intentions present in the early years of Kinzinger's work.

Around 1945, a new wave of artists less concerned with the spiritual began to dominate the American art scene. They replaced spiritual concerns with ones of a more concrete aesthetic nature. American artists of this new generation began to look to beliefs and traditions more associated with native and non-western cultures and less with the European theories and spiritual philosophy that had their roots in Theosophy. For the first time it seemed possible to make an abstract art without reference to spiritual matters. Kinzinger's world had once again shifted beneath his feet. He ceased painting around 1950. Often ill late in his life with depression, Kinzinger resided in various locations until his death on April 18, 1963.

We can only speculate as to why the later Kinzinger works, those after 1940, seem to lack the vibrancy and sincerity of the early works. The losses he suffered and the changes he endured were surely enough to dampen the most creative spirit. Even Kinzinger himself may not have recognized the moment when the essential dynamic spirit of his work slipped away. Whatever the case, the early works show us an art, truthful to its time and possessing an intelligent grace and power — even sweetness. It is an honesty and beauty that still engages us as human beings almost eighty years after the works' creation. Made during an often harsh and troubled moment in history, they stand as testament to the dazzling promise and deeply felt experience of a human being who had tried to decipher the ineffable meaning of life.

Philip Van Keuren

Director, The Gallery

August 1992

This small exhibition and brief essay are not intended to show or discuss Kinzinger's work with the depth it deserves. It serves merely to begin what is a long overdue re-evaluation of his contribution as an artist and a teacher. The installation of many of the works is also intended to reveal and examine Kinzinger's very early use of serial imagery. Only a very small handful of artists had worked in such a way by 1930. Serial imagery would much later become a powerful impulse in American painting around I960. In serial imagery each work is complete in itself; however several works may share certain standardized, structural pictorial elements while at the same time conveying different moods through the use of color.

The earliest use of such serial imagery would be Monet's series of paintings Haystacks and Poplars in 1891 and the Cathedrals shown in 1895. Alexi Jawlensky, working in Switzerland, experimented with serial painting beginning around 1914 and ending in 1937. At approximately the same time the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian standardized many elements within his pictorial structure. Joseph Albers conceived of his first serial works, Treble Clefs, in 1931 while at the Bauhaus. While on the surface it may seem there is no connection beyond geographical proximity, the emergence of serial concerns in several artists may be linked to the friendship between Jawlensky and Kandinsky. Both were members of Der Blau Reiter, and Kandinsky was the dominant avant garde artist in Germany prior to the First World War. It seems inevitable that interaction with Kandinsky 's circle of students and artist friends would have occurred, and that Kinzinger would grasp the significance of these ideas and begin to find a way to incorporate them in his own personal impulse towards abstraction.

We are deeply grateful to our lenders to this exhibition, Kitty and Paul Baker and Irene Corey. We hope they share our pleasure in showing these works collectively for the first time. Without their generosity and helpfulness, The Gallery and this University would have great difficulty in presenting an exhibition of this quality. As a University we are again reminded of how essential it is that we remain a part of the community and that the community feel that it is a part of us. In addition, The Gallery wishes to thank the Dallas architect Richard Flatt, a close friend of both Irene Corey and the Bakers, who acted with great enthusiasm as an important intermediary and valuable source of information. I would also like to thank Mary Vernon, Chair of the Art Division of the Meadows School of the Arts, for her insightful editorial suggestions and comments.

Page 2 and back cover, Edmund D. Kinzinger: The Early Years 1913-1935 exhibition catalogue, The Gallery, Hughes-Trigg Student Center, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Texas, U.S.A., 1992

Cover and page 1, Edmund Kinzinger, Cubist and Other Works: 1910-50 exhibition catalogue, The Art Center, Waco, Texas, U.S.A., 1992

Pages 2-3, Edmund Kinzinger, Cubist and Other Works: 1910-50 exhibition catalogue, The Art Center, Waco, Texas, U.S.A., 1992

Pages 4-5, Edmund Kinzinger, Cubist and Other Works: 1910-50 exhibition catalogue, The Art Center, Waco, Texas, U.S.A., 1992

Pages 6-7, Edmund Kinzinger, Cubist and Other Works: 1910-50 exhibition catalogue, The Art Center, Waco, Texas, U.S.A., 1992

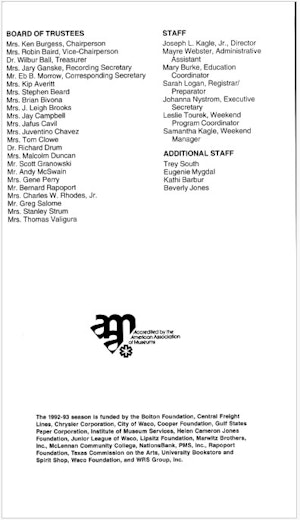

Page 8 and back cover, Edmund Kinzinger, Cubist and Other Works: 1910-50 exhibition catalogue, The Art Center, Waco, Texas, U.S.A., 1992