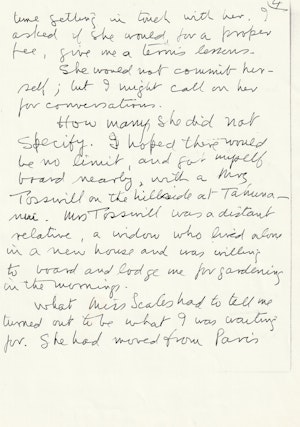

Pages 1-2, Tosswill Woollaston’s handwritten essay supplied to B. de Lange, 1992

Reproduced with the kind permission of the Toss Woollaston Trust, May 2021

1

When, as an art student in Christchurch, I mowed lawns for a Mrs Reeves and she invited me into the house for tea, I was very excited by some modern paintings I saw there, of streets in Paris. They were powerfully organised into the simplest possible shapes, the plane trees on the sidewalks for instance being rendered by a simple dark vertical for the stem, and a flat disc for the foliage. Who had done them? I asked.

Her sister, Flora Scales. There was another picture she drew my attention to, very different, a large copy of a famous English painting – I forget by what R.A. – of a woman in the wind, holding her hat in one hand and three dogs’ leashes in the other – “Diana of the Uplands” [Charles Wellington Furse (1868-1904), 1903-1904, oil on canvas]. This full sized copy of the original had been made by Flora “before she went mad”.

Mrs Reeves asked me if I would give her private art lessons, because she was too shy to face even the restricted public of an outdoor art class. So, for half-a-crown an hour and with her daughter Patty, we went up onto the Cashmere Hills to try the landscape. She had asked her sister for lessons, but had been refused. Her sister, she told me, would take only “serious pupils”.

I began to see why. When she looked at my drawing and said “Oh, Mr Woollaston, how do you do those sweeping lines!” but still made her Southern Alps equal all across the paper, like the teeth of a saw, I realised that she was incapable of taking even my instruction seriously.

But she remembered me. The next winter, when I was in Mapua wondering where to go or what to do next for a needed new stimulus, a letter came telling me that Miss Scales was staying with a Mrs Rutherford, in Tahunanui, a suburb of Nelson. I wasted no time getting in touch with her. I asked if she would, for a proper fee, give me a term’s lessons.

She would not commit herself; but I might call on her for conversations.

How many, she did not specify. I hoped there would be no limit, and got myself board nearby, with a Mrs Tosswill on the hillside at Tahunanui. Mrs Tosswill was a distant relative, a widow who lived alone in a new house and was willing to board and lodge me for gardening in the mornings.

What Miss Scales had to tell me turned out to be what I was waiting for. She had moved from Paris to Munich, where she attended the Hans Hofmann School of painting. When I told her how excited I had been by those Paris paintings at her sister’s, and she repudiated them, saying – “You can see everything in Paris; but you can learn everything in Germany”, I felt reproved for my calf-like admiration. I paid all the more attention to what she had to tell me now.

It turned all my previous art instruction upside down. It abolished vanishing perspective. It ruled out the idea that it was good, or even possible, to copy nature perfectly. What you had to do instead was create space in terms of the physical two-dimensionality of the picture plane. Objects in a landscape must not recede into the distance, getting paler and smaller. She showed me a painting of her own, done from the Tahuna hillside, in which the hills on the other side of the Bay at Separation Point (30 miles distant) were as strongly drawn and coloured as the foreground. I was amazed at the strength of a red she had used on them, where all the painters I had known before put pale blue. The violence of this release from convention and construction made me feel like a prisoner who had just broken the ropes he had been bound by. I walked up the newly gravelled road to Mrs Tosswill’s house absorbed in the notebooks Miss Scales had lent me to read and copy out. (There was no traffic in those days – Mrs Tosswill’s was the last house.)

There was a statement in one of these books of lecture notes, in the quaint English of a German lecturer, that vanishing perspective was “the fatal inherity of the Renaissance”. (Printers, please do not “correct” that to “inheritance”.) In conversation, Miss Scales supplemented that statement by explaining that there is greater space further from us than nearby – only yards at our feet, but miles in the distance – and diverging lines correspond better with our feeling about that than converging ones.

I have often thought about Chinese and Japanese art in that respect: they draw the building or the street as it really is – the same width right along, not narrower at the further end as it only appears to be. I have coined a word – “appearancism”, to replace the false word, “realism”, about that. Architects are at last coming right in their drawings of projected buildings – they draw them as they really are, not as they would appear to an eye at one end of them – and so make them much more comprehensible, as well as saving themselves unnecessary and teasing problems about vanishing perspective. (May it vanish altogether from the practice of art!)

There was a fascinating story in one of the notebooks about a European artist, Miss White, who visited the court of the Chinese Empress, where she had a friend who was a Court Lady. She got her friend to persuade the Empress to sit to her for her portrait. But after the first sitting the Empress declined to sit again, no reason given.

When, because of Miss White’s distress, the Court Lady did an unprecedented thing, she asked the Empress her reason for not sitting any more – the explanation was a simple one: she couldn’t have posterity believe that half her face was dirty!

Miss White had painted the shadow in the European tradition, and the effect was shocking to a Chinese-trained eye that sees the actual colour and disregards the shadow as unreal. Miss Scales told me I must not use shadows for modelling, I must make the form out of the proper relationships between lines, planes and volumes. Space comes from movement, when these are properly related. (“A point moves, and becomes a line: a line moves, and becomes a plane; a plane moves, and becomes a volume”.)

When she was showing me a reproduction of a head by Picasso and I pointed out that a very dark passage looked like shadow to me, she countered – “Yes, but not too much shadow” – I puzzled it out eventually that she must have been saying that Picasso had transformed the shadow into a dark to contrast with his light, rather than using it for modelling the form in the old academic way.

When I brought my own work for her to criticise, she would preface her remarks with, “Very nice – but –”, and tell me, for instance, how I had failed in my drawing of a row of pine trees, to use them as overlapping planes to make space.

To impart such an intellectual idea into the use of nature was exciting indeed. It was like being given a shovel to scoop up what before I had only had my hands to scrabble in. Ideas I called tools of the mind. Technique was transformed for me from tools of the hand, to tools of the mind.

She pointed out to me how in Cézanne’s painting the verticals were never so exactly vertical that you did not feel their contrast with the frame. Nor his horizontals; they made space by being just enough different from the top and bottom edges of the picture for you to feel a movement towards them in space. And, in still-lifes, a line, say of the further edge of a table, would reappear from behind an object on the table – say a vase or dish – at a slightly different level on one side from the other. This was not because he “couldn’t draw” (as Hugh Scott had tried to tell me) it was a profoundly considered and deliberate space-making device.

(When, after getting this knowledge, I took a water-colour I had done to Mr Savage, of Hardy Street, Nelson, to be framed, and he offered to trim the edge so as to correct an offending vertical, I had to use strong words indeed to prevent his doing any such thing.)

“Draw for a month”, directed Miss Scales. Then, when your drawing is right, put a grease-proof paper (semi-transparent) over your charcoal drawing and trace it on that; then transfer it to canvas. (I forget how you were to perform that feat. By sticking pins through it and connecting them afterwards by lines?) Whatever the method, I never tried to perform it. Long before a month, Miss Scales had put an end to my visits. And I was never able to find any conviction in myself to alter a drawing so many times.

Miss Scales, in doing it herself, used many sticks of French Vine Charcoal. She used them down to the very end, finally pushing a small piece round on the paper with the tip of her finger, until it disappeared. She advised me to do the same, to save money, “For you-know-what, Mr Woollaston.” She had advised me to go myself to the Hans Hofmann School in Munich. I could not take seriously the thought of how many ends of charcoal not thrown away it would take to equal the fare to the other side of the world and back – nor see myself doing that many drawings in time for such an expedition to be of use.

When I reiterated, pleadingly, my request that she give me a term’s tuition, Miss Scales told me of an “Academie Scales” she hoped to establish the next year in Wellington. I might enrol in that.

It never eventuated.

She qualified her advice, too, about going to Germany. It was not a good time. She had “seen Hitler’s men marching”.

She had never actually invited me to visit her at Mrs Rutherford’s. I just turned up at the door each afternoon. I suggested to her that it would be wonderful if she came out to Riwaka to paint. There were hills there, and it would be fascinating to me to see how she would treat a landscape I knew well, but hadn’t had the means to paint as I wished.

Her answer was that she could not – if she sat on a hill where there no houses she would feel as though a hand might clutch her from behind.

I was so absorbed in what she was telling me that I probably missed signs that my visits were becoming less desirable to her. Four visits, all seemed to go well, but on the fifth she answered my knocking very tardily, put her foot in the door and held it closed all but her shoe’s width, and talked to me through that aperture until I had to go away, realising that the visits were over.

What was I to do?

There was plenty. I had my copies of her lecture notebooks, that I could pore over and extract more and more from. And a brilliant idea occurred to me; the Spring Show of the Suter Art Society would be coming up soon – I would tell them about this wonderful painter from a very well respected family (Mrs Every had told me about the Scales Shipping Line – and how “Old Lady Scales” sat on a promontory, I think outside Wellington, and prayed over every ship that went out, and they never lost one) – who was staying in Nelson, and suggest that they might invite her to be their guest exhibitor.

They swallowed the bait – and so I had a fortnight during which I could go to the Gallery and look at her pictures every day. The Art Society people hated them; but they were the only things in the show I found it constructive to look at. One of them was a drawing at the grease-proof paper stage. The strains of the process had torn the paper, and the artist had pinned the torn edges in place with drawing pins. This sort of presentation proved to the people how shocking these pictures were. That an artist should have things on her mind that made a tear held together with pins not matter was something that could not find room in their thoughts. “Like frying-pans!” was the best thing an Art Society stalwart – Marjorie Naylor – could find to say about them. Art only fit for a kitchen!

When Rodney Kennedy came up from Dunedin for the 1935 fruit season, he was very interested in the change in my work. Though I hadn’t done a lot – I had been building a studio out of sun-dried clay bricks to live and work in – the change in what there was was well beyond what had been the result of my visit to Dunedin in 1932. “We didn’t teach you anything!” was his verdict the following year, when I had such a body of work that he urged me to have a show of it in Dunedin, it was so much more modern than they were, who had been so much more modern than the rest of New Zealand.

That show was a success, in that it impressed the discerning. I had read, and taken to heart naturally, a warning in one of Miss Scales’ notebooks against “using the forms of modernism as fashion”. I can honestly say I have never done that. In time I was to be considered old-fashioned, after having been too modern for the general public in the thirties and forties.

When the Second World War came I was working on an orchard in Mahana. It was not for nothing Miss Scales had warned me about “Hitler’s men marching”. My employers were the Jacksons. Mrs Jackson’s mother was a Mrs de Castro, of Blenheim. “Let me tell you,” said Miss Mellett, of Mellett’s Bookshop in Nelson, when I told her the name of my employers – “you are working for very high and mighty people!”

Well, this Mrs de Castro, on a visit to her daughter, showed no reluctance to talk to the orchard hand who was an artist. She was as garrulous as the sparkling little waves of the estuary sea below the orchard when the sun shone on a full tide in the morning. She told me that Flora Scales had died in internment in the Vosges Mountains of France.

2

My relations with the Auckland City Art Gallery began in 1957, when, feeling isolated in Greymouth I went to a summer-school run by Colin McCahon and Peter Tomory. Twenty-three years then, I had been working with the ideas of Hans Hofmann as given me by Flora Scales. At that summer-school, I didn’t find anything to replace them. I remember sitting in a wide half-circle of students drawing a nude male model (very professional, that!) listening to what an instructor, still too much steeped in academism, was saying to pupil after pupil about their drawings, and being unable to anticipate calmly what would happen when he came to me. An enormous pressure built up in me. It made me, when he was three pupils away, leap up out of my seat and go into the park, pretending I would rather draw there than from the model.

Of course I found nothing to draw in the park, I could only sit there while peace and isolation cured my agitation.

Colin McCahon, then embarked on his career of fame, thought I had come to pay him homage and learn from him. (My coming to the school at all would have justified him in that assumption.) He greeted me, when we met at a first-night party at Peter Tomory’s house, with a holding of hands while we walked across the room that made a woman witness say, “Ooh!” – as if she was drawing everybody’s attention to a greeting between male lovers.

I could get nothing from Colin’s painting that would serve mine. If I was any good, we were side by side, not one after the other. That summer-school was good for fun and parties and meeting people, and began what has been for me a fruitful relation with the Auckland City Art Gallery.

When, three years later, the Friends of the Gallery asked me to give them their Annual Lecture, a major part of it was about my indebtedness to Flora Scales. But I balanced it with criticism. Remembering her repudiation of those Paris paintings I had admired, and mindful that I had heard later that she had gone to St Ives in Cornwall to study under Stanhope Forbes – (“Kind Mr Stanhope Forbes” – how I came to hear that remark of hers quoted I can’t remember any more) – I told my audience that she seemed to be an inveterate art student, going from influence to influence (like a bee from flower to flower?) – but that she was a very clear mirror of whatever she was influenced by at the time, and how lucky I was that it was Hans Hofmann when I met her. They published my lecture, called “The Faraway Hills”, in 1962.

Then, about 1970, Peter McLeavey told me that Miss Scales was not only still alive, she was living back in New Zealand.

In 1973 [sic 1975] the Auckland City Art Gallery mounted an exhibition of her work. Brenda Gamble, then Secretary, wrote a foreword to the catalogue – she sent me a copy – in which she placed Flora Scales in the chain of New Zealand modern painting, as having influenced me, and, through me, Colin McCahon at the beginning of his career.

Brenda also submitted a copy to Miss Scales for her approval, and wrote to me in great distress, quoting Miss Scales’ reply: – “I do not want Mr Woollaston’s name mentioned in connection with my exhibition. Whatever I may have said to him in 1934, and whatever he may have made of it since, is nothing to do with me.”

So, that was that. Yet I could not but admire her, for a spirited old lady. Ron O’Reilly, librarian, historian, and art critic, tried to persuade me to write her a conciliatory letter. He would dearly have liked to see what would come of a renewed relationship between us. I knew it would be no use, and told him repeatedly so. But Ron, when he got onto an idea, was more persistent than any dog with any bone, and eventually I had to write the letter if I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life in the sound of his nagging. Of course I got no reply.

I didn’t keep a copy of my letter. If it still exists among Miss Scales’ papers (which I doubt) it may be apparent to readers that I wrote it in the lack of any conviction that it could really mend matters.

3

Though Miss Scales had not actually died in internment in the Vosges Mountains, I learned from relatives and friends of the family that she had had a very bad time there, and worse in Paris for two years afterwards. Caught on her way with a friend to Portugal (for painting) in Paris when the Germans occupied it, she was put on a train at midnight for an unknown destination. “It was funny,” she observed, “to see women asking men working on the line if they knew where their train was going to.”

She survived on Red Cross food parcels, becoming so attached to them that it seemed “like a death sentence” when she was ordered to go back to Paris where she wouldn’t get any. For two dreadful years she survived by joining food queues at shops where more often than not the food had run out before her turn. Not being French, she was pushed to the back of the queue. To be warm she went to a drawing class for German students, where, she reported, not much drawing was done. It was the warmth that attracted them, as well as her.

When her friends and family met her in London at the end of the war she was in dreadful black clothes the French had given her, and shoes that didn’t fit, and there was no spring in her walk! She had brought her rations of salt and potatoes with her because she had been told that they were starving in England. It took many weeks of careful feeding – at first she couldn’t eat much because of her shrunken stomach – “to get the spring back into her walk”.

But when they took her to Harrods to buy clothes, “all her old taste was there, and she chose a suit of beautiful heather coloured tweed.”

When I saw the 1973 [1975] exhibition of her work at the Peter McLeavey Gallery in Wellington I revised my estimation of her as an inveterate student. The pictures were all small, beautiful and sensitive evidences of an artist’s personality. Nobody else could have painted them. I would dearly have liked to acquire one or both of her self-portraits with the head tilted to one side not only laterally but in depth, so that your vision moved with it in deep space – but they were gone before I got to the exhibition. I bought a picture of anemones [BC051] instead – the one I found I remembered best after a day or two. It is still as beautiful as when I bought it.

I have been lent three books totalling a hundred and twenty [heavily mounted] photographs of Miss Scales’ work as material for writing this article. They range over the whole life, book 1 being half of very competent and sensitive, though academic, studies of animals (horses mainly – one of cows under trees) and seascapes – clearly done before her Hofmann influence. The second half of this book, with dates ranging over the 1930’s, shows how she was painting when I met her.

The second book jumps to the 1950’s, and there is a change that is all-pervasive but hard to describe, “looseness” is too negative a word. “Freedom” is too vague and general. The latest date in it is 1976 – so that it trespasses, chronologically, on the territory of the third book, whose latest date – 1983 – must be the last year of her life. For I am sure she painted right up to the time of her death, in spite of increasing difficulty in seeing because of cataracts. “I can’t see very well today” she told a friend, by way of accounting for imperfection in her work.

What sort of imperfection would she have meant? Apart from the sense of failure an artist always feels from aiming higher than it is possible to achieve, these works are, in my view, very perfect of their kind. There is not a brushstroke but that gives us the feeling of a bird having just alighted on a bough that is still quivering from the impact. Because the hand had to do so much for the failing eye, there is a greater immediacy in these works than in any before. The hand touches, whereas the eye is at a distance from what it sees.

There is a cat, dated c.1976 [BC082, BC083], in which the hand has its say as much as, if not more than the eye. It is much nearer to us than those competent horses of the first period of the artist’s life, parading so properly in their appearances which fit them like tight tunics, jerseys – or even wet-suits! This cat is lying so relaxed, hind feet away from us, that we hardly think of its appearance at all; or, if we do, only as an effect of the pulse of all creation. That its life and its appearance coincide so beautifully and easily, gives the latter a quality of comfortable, loose-fitting clothes being worn casually and yet with consummate style. Bravo, Flora! You were on the way, in these last paintings, to where life flows without interruption or impediment – even the impediment of having to paint it.

There are portraits, in pencil, coloured crayons and one in oils, of family and friends – a man named Theo [BC111], a child called Sophie [BC110], and a little boy called Jacob [BC084].

Jacob’s is the one in oil – a round-headed little boy looking at us over his shoulder. His clothing is blue, his eyes dark, mouth red, and face luminous broken yellow with white, blue, red and brown breaking it in touches and flecks. The background and his hair are brown, varied with strokes of blue and red – so subdued that we “scarcely see, we feel” that they are there. Nothing is hard-edged, nothing insists on the limitations of its own shape – and the effect is unlimited.

(My quotation, from Shelley’s Ode to a Skylark [To a Skylark by Percy Bysshe Shelley, 1820], was prompted by the kind of exultance this painting produces in me, similar to Shelley’s in that poem.)

Sophie is done in coloured oil crayon on paper with an arrangement of strokes that yields, on analysis, a composition that, though very simple, is also very subtle and interesting. There are two sets of strokes, one blue and one brown, that are only slightly varied from the vertical. The blue strokes, all in the background except one that comes forward emphatically to define the neck, appear longer than the brown ones, which are in lateral bands, representing the hair. Contrasting with these two kinds of vertical strokes are single horizontalish lines, long ones for the top of the head and for the lower part of the face, and short ones to define the features. The benefit of a lifetime’s attention to construction is in this apparently simple drawing of Sophie – whose image, spontaneous as it looks, is very well served by her great-aunt(?) Flora’s profound knowledge of the principles of art that saturate this simple-looking drawing.

As her sight failed her pictures became more beautiful. It seems as if a spirit, having the use of her hand more and more to itself, set out to prove the eye an encumbrance.

Even in pictures where most people would say the process goes too far – of Theo for example, and a woman in a green dress [BC095] – there is a similar sort of pleasure to be had to that we take in the art of young children. It is not merely freedom for its own sake we admire, but the very clear expression of a world of innocence. Gone is the mastery of expression in the painting – dated 1960s – of a “Seated Woman” [BC036]. She is wearing a red beret and a dark jacket. Her hands are folded in front of her. The whole atmosphere is of the artist’s social superiority to the sitter. It is not insisted upon, consciously perhaps, but it is there.

In the Rotorua “Woman in a Green Dress” [BC095] the artist is humble before her subject, beaten into helplessness by her failing powers but nevertheless persevering to paint. The result is paint given liberties it never knew before. We begin by being tempted to criticise incompetence; but end by appreciating in spite of it the unique personality of this artist.

For the value of each artist is in being like no other. “Not mood in him nor meaning”, as the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins points out, writing of Henry Purcell – “proud fire or sacred fear/Or love or pity or all that sweet notes not his might nursle,/ It is the forged feature finds me, abrupt rehearsal/Of own self so thrusts on, so throngs the ear” [sic] (Henry Purcell by Gerard Manley Hopkins, 1918).

“Own self” in painting – as apparently in music – is not egotism. It appeals less to the crowd than those other values, Manley Hopkins’ sample of which – “proud fire or sacred fear/Or love or pity” is a more meritorious bunch than what often does lead the public away from art in pictures that use some social message, or anger with society, or – at the lowest ebb – flattery in portraits of socially powerful sitters.

You cannot put the precise definition of the subject in front of the painting in these late pictures by Flora Scales. There is no “social message”, nothing to help you to run away from pure contemplation of the painting. This “self” is a good one. My instant thought – “I wish I could paint like that!” – is curbed by the realisation that if I could it would not be me; and to be myself is the best compliment I can pay to another artist.

Tosswill Woollaston, 1992

.jpg?ixlib=js-3.8.0&auto=format&w=300)

.jpg?ixlib=js-3.8.0&auto=format&w=300)

.jpg?ixlib=js-3.8.0&auto=format&w=300)

.jpg?ixlib=js-3.8.0&auto=format&w=300)

.jpg?ixlib=js-3.8.0&auto=format&w=300)

.jpg?ixlib=js-3.8.0&auto=format&w=300)

.jpg?ixlib=js-3.8.0&auto=format&w=300)

.jpg?ixlib=js-3.8.0&auto=format&w=300)

.jpg?ixlib=js-3.8.0&auto=format&w=300)

.jpg?ixlib=js-3.8.0&auto=format&w=300)

.jpg?ixlib=js-3.8.0&auto=format&w=300)

.jpg?ixlib=js-3.8.0&auto=format&w=300)

.jpg?ixlib=js-3.8.0&auto=format&w=300)

.jpg?ixlib=js-3.8.0&auto=format&w=300)

.jpg?ixlib=js-3.8.0&auto=format&w=300)

.jpg?ixlib=js-3.8.0&auto=format&w=300)

.jpg?ixlib=js-3.8.0&auto=format&w=300)

.jpg?ixlib=js-3.8.0&auto=format&w=300)

.jpg?ixlib=js-3.8.0&auto=format&w=300)

.jpg?ixlib=js-3.8.0&auto=format&w=300)

.jpg?ixlib=js-3.8.0&auto=format&w=300)

.jpg?ixlib=js-3.8.0&auto=format&w=300)

.jpg?ixlib=js-3.8.0&auto=format&w=300)

.jpg?ixlib=js-3.8.0&auto=format&w=300)

.jpg?ixlib=js-3.8.0&auto=format&w=300)

-1728438223.jpg?ixlib=js-3.8.0&auto=format&w=300)

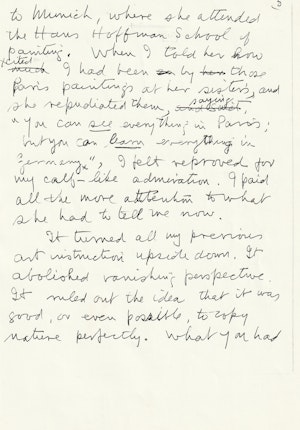

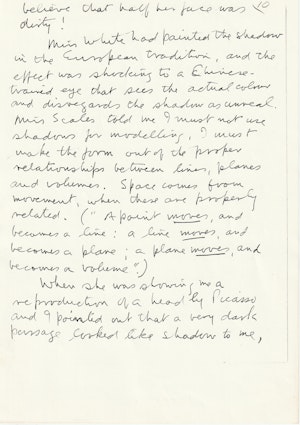

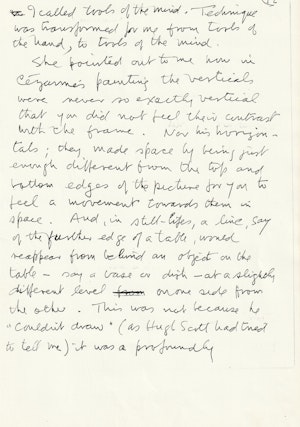

Pages 3-39, Tosswill Woollaston’s handwritten essay supplied to B. de Lange, 1992

Reproduced with the kind permission of the Toss Woollaston Trust, May 2021