Flora Scales painting outdoors, Pihautea, Wairarapa, New Zealand, April 1906

Photo: Bidwill family album

![Untitled-[The-White-Horse]_35A6020_crop-no-frame.jpg](https://florascales.imgix.net/Untitled-%5BThe-White-Horse%5D_35A6020_crop-no-frame.jpg?ixlib=js-3.8.0&auto=format&w=300)

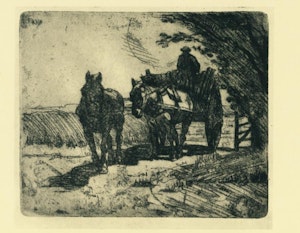

Fig. 1: Flora Scales, Untitled [The White Horse] [BC003], 1908 – 1912

For Patty Tennent and Marjorie de Lange

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I had the great pleasure of meeting Flora Scales in the summer of 1975, soon after the opening of her exhibition at the Auckland City Art Gallery. Having seen her exhibited paintings and heard a little of her life story, I gladly took the opportunity when it arose, to study both in more detail.

An attempt to assess Scales's status as an artist must necessarily be less than complete due to the loss of a large proportion of her work from the 1930s, a particularly vital and productive period of her life. Yet sufficient survives to affirm that Scales was among the most interesting and adventurous of New Zealand's expatriate artists, whose understanding of European Modernism formed the cornerstone of all her work after 1932. I have hoped to show, from the documented facts of her life and the richly evocative memories of those who knew her, the attitudes and circumstances that shaped her career. With the telling of her story she takes her place, quietly but securely, as a Modernist painter in her own right and crucial to the development of Modernism in New Zealand art.

In the course of my research for this work, I have been greatly assisted by Mrs. Patience Tennent and all the members of Scales's family in New Zealand. I thank them most sincerely for their faith, forbearance, and friendship.

I wish to acknowledge most gratefully the support and encouragement I have received from my family, friends, and the owners of Scales's paintings.

I am also grateful to the staff of the following institutions for their efficiency and helpful assistance: the Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand; the Research Library of the Auckland City Art Gallery; the Auckland Institute and Museum Library; the Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, Texas; the Canterbury Public Library; the Dowse Art Gallery; the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery; the Heatherley School of Fine Art, London; the Lower Hutt Public Library; the Manawatu Art Gallery; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the National Art Gallery, Wellington; the Nelson Provincial Museum; the New Zealand Academy of Fine Arts; Marsden School Library; the Robert McDougall Art Gallery; the Rotorua Art Gallery; the Sarjeant Gallery; the School of Fine Arts Library, University of Auckland; the Library, University of Canterbury, Christchurch; the Fine Arts Department Library, University of Canterbury, Christchurch; the Hocken Library, University of Otago; the Victoria University Library; the Wellington Art Club; the Wellington Public Library.

Special thanks are also due to the many people who willingly gave their time and attention to further this project, including Mary Hall, who provided encouragement, a leavening humor, and practical assistance at all levels; Maree Gunn and Marianne Sangster, who brought the manuscript to order; Boris Kalachnikoff and Sir M. T. Woollaston, whose personal memories extend the dimensions of my work; and Serge and Jenny Kotlarevsky, who translated Boris Kalachnikoff's essay and correspondence with the author with skill and sensitivity.

I am particularly indebted to Gordon H. Brown, who so generously and beneficially lent his scholarship and expertise to my project.

___

INTRODUCTION

During the research for this book, my mother-in-law, Marjorie de Lange, undertook the pleasant task of asking Flora Scales for some memories of her long life. The detailed notes from their conversations include an account of the artist at work on a portrait of Theo, Marjorie's husband:

“She looks so composed sitting straight as a die in her white calico artist's smock with a high ruff collar, completely in control, her eye penetrating and her hand steady. She says: ‘Now I am thinking. I spend a lot of time thinking but this is actually work. I try to forget the subject and think only of the painting.’ She visibly bristles with concentration and says every stroke is important. She has ultramarine blue, light red, yellow ochre, and some white on her palette, but she only uses the red. The canvas board is about 20 by 16 inches [50 x 40cm]. The light and heat are dreadful. When it's time to stop she says: ‘Leave it on the easel and I will do some work on it from memory.’”¹

Here we have Flora Scales at the age of ninety-five demonstrating a conviction so important and dear to her heart that when she saw Marjorie writing it down she told her to "put it in a box" so it would not be overlooked.

"You must hold on and hang on absolutely."²

Fig. 2: Flora Scales, Overlooking the Bay [BC006], c.1920-1925

Fig. 3: Flora Scales, Homecoming [BC124], c.1914-1921

THE EARLY YEARS

Helen Flora Victoria Scales was born in Lower Hutt on 24 May 1887. She was the second of five children and the elder of two daughters.

Her father, George Herbert Scales, had arrived in New Zealand in 1879 at the age of twenty-one, "a gigantic, raw-boned youth...nearly six feet three inches in height."¹ Within a few years, by dint of his driving ambition and sheer hard work, this charming, personable son of an English gentleman had successfully established himself in business as a stock salesman and auctioneer, hemp broker and insurance agent.² In 1884 he married Gertrude Maynard Snow, the youngest child of Charles Hastings Snow. With his family and full retinue of staff Snow had arrived in 1860 on the Lord Burleigh to take up the post of Government Surveyor. Scales's marriage into this cultured, aristocratically connected family ensured him the position in the upper echelons of Wellington society to which he had aspired.

In their early years together the couple lived at Atiamuri, on the site of what is now the Hutt Recreation Grounds in Bellevue Road, Lower Hutt, and George Scales, full of verve and dash, was often to be seen, "spanking along in a very high dog cart with always two or three dogs following."³

Later, towards the turn of the century, with the greater prosperity afforded by his position as Secretary to the Committee of the Freight Reduction Movement,⁴ he moved his family to Kuhawai, the house he had built on five hundred acres of land in the Western Hutt hills. A friend's contribution to the family scrapbook gives some idea of the singularly beautiful, if unconventional, situation he had chosen for his home:

"We were very interested when Mr. Scales built a new home on a hill, half-way between Lower Hutt and Petone. To get to it you had to walk quite a distance from either town. First you crossed the railway line at White's Line, then plodded up a long drive cut out of the hillside. Once there the view made up for everything.

Below in the distance were the lovely grounds owned by the strange Percy family which are now public gardens. Right away as far as you could see was Wellington Harbour with Soames Island [Matiu Somes Island] in the centre and the Heads with ships coming and going. Wellington Harbour is a very deep blue as seen on a fine day.

The drawing room windows looked out on all this and visitors were fascinated because, in those motorless days, it was thought that a hill was a place to climb, not to live on. Beautiful native New Zealand bush with ferns and bent tree trunks looked very lovely just near the front door and there were little paths leading to nooks and ferny spots and plenty of birds."⁵

In these lush and luxurious surroundings, the Scales family enjoyed the pastimes of Edwardian upper middle-class life. George and Gertrude were especially keen on sport. Gertrude was a first-class golfer who also excelled at tennis, while George was passionate about croquet and inspired their visitors—the Riddifords, Fitzherberts, Purdys, and Kirks—with equal enthusiasm for the game. There were also memorable parties along the lines of the one described by another family friend in the scrapbook:

"A great friend of mine and I were very thrilled, as girls of about seventeen, to be asked to a private dance at the Scales's house. We had to carry our dancing shoes in a bag and walk, but everyone did that. It was pitch dark going up the drive and I think some fell down the bank. Often guests would fall down the bank going to parties up hilly drives and muslin frocks would be daubed with clay and mud. I remember being struck with the Scales's home as we arrived. Lights were on everywhere and the large panelled hall was lit by lights covered with long shades of scarlet crinkled paper which looked so romantic. Seats for the sitters-out were in the hall and also on the dimly lit side verandah. As Mr. Scales had lit the bush paths with Chinese lanterns, many strolled there and passed the time o’day and some lingered too long. Later in the evening, strolling was so popular that the music struck up in vain to an almost empty room.

I heard that Mr. Scales said wrathfully of the dance the next day, 'blooming garden party'."⁶

Animals were regarded as part and parcel of the bustling family life. Flora's niece remembers her father [Athol Scales] telling her that "their home was full of dogs, mostly strays that Lassie [as Flora was always called] had taken under her wing..." and there were ponies on which the children learned to ride, though her brother was of the opinion that, "Lassie was about the only girl who sat a horse properly and didn't look like a sack of potatoes."⁷ Flora's love of animals never waned; cats, dogs, and horses came trustingly to her, and she was never happier, as friends have reported, than when being smothered with doggy kisses.

Gertrude Scales took lessons in painting from a friend, Miss Mary Allen, who came to the house, and Flora remembered admiring a painting of a "lovely white gate" her mother had painted to raise money for charity.⁸ But it may well have been the constant example of her father's rather successful drawing of the famous racehorse Samodrid, in pride of place on the dining room wall, that inspired her to "paint horses in the paddock from the age of about seven."⁹ This natural inclination to be always drawing was encouraged with private lessons, and she practised assiduously to improve her powers of observation and memory. She remembered, at the age of twelve, "leaning out of a window drawing a horse. A man visiting my father said it was too long and shortened it by folding the paper like a concertina. On reflection, I think it is a good thing I noticed and observed the horse."¹⁰ A friend recalled, "Lassie drew most beautifully, especially horses, some of her watercolours of horses were quite perfect."¹¹

George Scales, a self-made man described by his friends as "well-read and interesting" with a "wonderful brain,"¹² had a great deal of respect for those with the advantages of sound education. He once remarked to the wife of his friend Professor von Zedlitz that, "he'd give anything to have her husband's knowledge,"13 and feeling this want in himself determined his children would have the best education available.

As a young child, Flora attended the Private Day School conducted by Miss Haase in the St. James's schoolroom, Lower Hutt, where the subjects included English, French, Latin, drawing, painting, music, and needlework—plain and fancy.14

When she was about ten years of age, she progressed to Miss Swainson's school at No. 20 Fitzherbert Terrace in Thorndon, Wellington, which was the academically enlightened precursor of the present-day Marsden School in Karori.15

In 1903, at the age of sixteen, Flora was sent to board at Miss Croasdaile Bowen's School in Christchurch.16 While there, to develop her evident gift for drawing, she enrolled at the Canterbury College School of Art, attending three terms of evening classes in her first year and, in 1904, taking afternoon classes as well.17

The life class she attended in the third term of her second year was remembered with particular clarity by Scales, "When dear father realised I would be working from male and female nude models he arranged for Richard Wallwork, a tutor whom he knew, to take me for my first lesson with a male model. My father was also present for this lesson."¹⁸

At the Art School, then headed by George Herbert Elliott, Flora Scales would have been fully instructed in the all-important "scientific principles"¹⁹ of art set out by the examining body of the Education Department of Great Britain to which the School was affiliated.²⁰ There are no records that she sat any of the examinations offered by the Department, but these were, after all, primarily for students wishing to qualify as teachers and Flora did not include that in her plans for the future.

Flora and her father seem to have understood each other well and formed a particularly close friendship within the family. Perhaps it was he who affectionately nicknamed her Lassie, as if to keep her forever young and bright and thinking the world of him. Scales told Marjorie de Lange of a game she and her father had invented when he, returning at night with fish for the family dinner, would throw it out of the window of the moving train, and she, waiting by the tracks on her pony, would catch it and gallop up the hill to be home and ready by the time her father arrived at the door. It sounds as if they had fun together and possibly George favoured her for her high spirits and love of the outdoors which, while she was tractable, would have made her an ideal companion.

He certainly had high hopes for her future. Just before turning twenty-one, Flora, who had become "a striking-looking girl with the erect poise of her mother,"²¹ received a proposal of marriage from the son of a neighbouring family, but was forced to refuse because "her father did not approve."²² There could be no going against him; his authority was total. As Flora wryly commented years later: "When Father turned, we all turned."²³

Although in this case the prospective bridegroom was unstable and patently unsuitable, George Scales may also have been reluctant to relinquish the position he held in his eldest daughter's life. Perhaps too, he felt that while she remained unmarried her artistic potential had more chance to flourish. "I want you to make something of your life,"²⁴ he told her.

Already, by 1906 and 1907, she had exhibited paintings at the New Zealand Academy of Fine Arts. Her ability in this field therefore seemed sufficiently promising to warrant sending her to London for further tuition in animal painting.

As well as a diversion from her foiled plans for marriage, her family thought that such a course of learning would provide her with an absorbing career, without compromising her social position, once she returned to New Zealand, and the Calderon School of Animal Painting was duly approached.²⁵

By 1905 the genre of animal painting in New Zealand was sufficiently well established by both male and female artists to assure them of continuing commissions and financial security. The wealth accumulated from improved agricultural methods and the establishment of a more secure commercial world had brought with it the desire to have the accoutrements of such prosperity permanently recorded. Artists might be requested to provide accurate and anatomically detailed portraits of valuable animals, or a more romantic, often sentimental and anthropomorphic study might be preferred. George Scales, looking to the future, may well have been seduced by these prospects and by the idea of himself, the proud father of a successful animal painter, accompanying his daughter as she travelled about recording the figures of valuable bloodstock.

Fig. 4: Flora Scales, Untitled [Pink Tree, Village and Bay] [BC015], 1931

Fig. 5: Flora Scales, Untitled [Two Green Trees] [BC014], 1931

AN ART STUDENT IN LONDON

In 1908 Flora travelled to England with her father (who was to arrange steamship charters for the transportation of New Zealand wool to England).¹

Scales remembered her father "bursting with ambition for me,"² but she had less drive and belief in her future and felt that she, "only wanted to draw horses. I hadn't the art, I only thought about horses."³ Looking back at herself and her work of this period, she felt she had been dull and unimaginative: "What a dunderhead I was never once to have put in a tree or a blue sky above the animal,"⁴ she said.

In spite of any doubts she may have personally harboured about the extent of her artistic abilities, she was accepted at the Calderon School and later described some of her experiences there:

“In London there was a big place like a room; the horses were brought in from a nearby mews. Upstairs Mr Calderon kept dogs which we used to draw.⁵

In the summers we went to Norfolk by train, about ten students. Some were outsiders, amateurs, who really went for the holiday. We were billeted in local cottages. Mr and Mrs Calderon were in a separate cottage. Mrs Calderon was a darling. At the end of the time Mrs Calderon collected us all and took us all to the train, and when necessary, gave any of us who had misbehaved a big lecture.”⁶

Somewhat to her dismay, Scales found that the teaching at the Calderon School differed little in its classical approach from that she had experienced at the Canterbury College School of Art, where emphasis was given to perfecting the techniques of representational drawing.

William Frank Calderon, the founder and principal of the school from 1894 until 1916, was firmly entrenched in the ideals of academic art. He exhibited at the Royal Academy from 1882 and occasionally gave lectures there on animal painting. An example of his work, There's a Fox in the Spinney, They Say, exhibited at the Academy in 1895, shows how faithfully he adhered to the official style of late nineteenth-century art unaffected by the discoveries of the open-air painters and the Impressionists.⁷ As Scales observed, "Mr Calderon gave us lots of anatomy lessons but, bless his heart, he knew nothing of tones or values."⁸

Three horse paintings that have survived from this time [Fig. 1, BC001, BC002] show her subscribing to a conventionality she was later to discard. For all the accuracy of observation, they are static creatures; painted according to academic principles to convey depth and surface reality but without character or life. Scales had yet to realise that her increasingly skilful technique could become a means to an end, allowing her to paint a subjective response to her topic without sacrificing the information required for its identification.

Despite what she perceived as shortcomings in Calderon's instruction, Scales accepted a scholarship which extended her original two years of study to four. The confidence gained during these years, the economy, efficiency and accuracy of drawing, the sureness of touch and strong hand-to-eye coordination, were always to be valued attributes of her painting practice.

A noteworthy achievement for the young artist, and a fulfilment of her father's vicarious ambition, was the hanging of her oil painting, Cattle Mustering in New Zealand, in the Summer Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts in 1911.⁹ This painting of a, "white-shirted rider on a brown horse, riding away with, I think, a stock whip,"¹⁰ was purchased by her father to hang in his Wellington office. It has, since his death, disappeared without trace.

As a serious art student from the Colonies, Scales would have been bound to visit the galleries and museums in London, where, in those pre-war years, artistic production was at fever pitch. It seems likely she would have known about the Camden Town Group and the work of artists such as Walter Sickert, Orpen, and Augustus John at the New English Art Club, all of whom held a more liberal attitude to art than was to be found at the Royal Academy. She may also have seen the iconoclastic exhibitions of Post-Impressionism arranged by Roger Fry at the Grafton Galleries in 1910 and 1912, where paintings by Cézanne, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Derain, Picasso, and Matisse were shown. She may even have visited the Albert Hall where Kandinsky's work was exhibited in 1909 and 1910 as part of the Allied Artists Exhibition.

Whichever way her eyes were opened, she came to realise that: "There was colour to think of as well as anatomical accuracy,"¹¹ and her four years of study and independent discovery concluded with a firm resolve to extend her work beyond the narrow confines of idealised animal studies. She had become ambitious on her own account, "ambitious to paint the human figure," as she said.¹²

In 1912 George Scales was again in England on business and early in November Flora returned with him to New Zealand, crossing the United States by train to visit members of the Scales family and sightseeing at the almost completed Panama Canal during the course of the journey.

Her younger sister, Marjorie, was married in November 1913 and Flora settled into the position of the dutiful daughter at home, attending to household chores and keeping social engagements as well as doing a little painting and drawing. She later credited her considerate attitude towards those whose livelihoods were earned in service, to this period when she herself did a lot of the housework. As she said: "I learnt to appreciate what it entails and now try to be careful and not make demands."¹³

The stifling routine of Scales's domestic life was temporarily relieved by a visit to India and Ceylon with a friend. This gave her the chance to experience the life of the British Raj at first hand and numerous opportunities to paint polo ponies and racehorses, but sadly none of this work has survived.

Fig. 6: Flora Scales, Untitled [Loose Leaf Pages] [BC112], c.1930-1960, pg 55

Fig. 7: Flora Scales, Untitled [Colarossi sketchbook] [BC114], 1931-1932, pg 10

WAR YEARS IN WELLINGTON AND THE 1920S IN NELSON

During the First World War Flora Scales enlisted with the Voluntary Aid Detachment of the Red Cross. She was based at the Taumaru Military Hospital, Lowry Bay, Wellington, where, as is recorded in her sister's scrapbook, she thoroughly enjoyed the cooking tasks to which she was assigned. While there she found a light-hearted outlet for her drawing skills in The Taumaru Trifler [BC143], a magazine produced to entertain the staff and patients at the Hospital.1

Whenever she had time to spare she would visit the art galleries in Wellington, finding out as much as she could about art in New Zealand because her interest in painting and the world of art was rapidly becoming the most compelling factor of her life.

Scales had returned home eager to extend her horizons in art and in 1914 she joined the most active group of artists in Wellington, the Academy Studio Club, to take advantage of their lively programme of meetings, lectures and classes, including life drawing.2

The Club favoured a method of painting, indirectly derived from the Barbizon School, known as plein air. It had been promoted in New Zealand by the Scot, James Nairn, who exhorted his followers to "paint the thing as one sees it,"3 and whose example encouraged them to work broadly for "an effect, specially in relation to light and colour values, rather than a close objective analysis of the images making up the painting."4 This method, which he himself had arrived at under the influence of the Glasgow School painters, survived his death in 1904 and supplied for a time the change of direction Scales sought in her own move away from the "objective analysis" of her training as an animal painter.

In a landscape from this period, Overlooking the Bay [Fig. 2], Scales made clear her break with Calderon's demands for visual accuracy and strict, linear perspective by excluding much of the detail of the scene and focusing on the transient effects of coloured light and atmosphere. The vigour of the brushstrokes, the cropped edges and the aerial perspective indicate that this is indeed a direct and rapidly recorded response to the outdoors in keeping with Nairn's teachings.

At the Art Club Scales found a stimulating mentor in James McDonald, “a prominent and much respected member…”,5 with whom she studied etching [Fig. 3]. Among her fellow students in these classes was Mina Arndt who had left New Zealand in 1900 and, during her time abroad, had studied etching with the German engraver, Hermann Struck. She had also been influenced by the almost expressionistic style of Lovis Corinth, a notable German painter.6

The example of professional standards and European influence set by McDonald and Arndt proved beneficial to Scales's work and in 1921 she and Arndt were rated as New Zealand's "two leading women etchers." The review continued:

“Miss Scales shows in her etchings the same mental interest that is revealed in her drawings and paintings. Indeed no artist in the Dominion can delineate farm animals and scenes so well as Flora Scales. So far she has produced only a few etchings but already shows herself a competent worker with the copperplate.7

By the early 1920s Scales had gained high standing as an artist in New Zealand. In 1920 the art reviewer for the New Zealand Times labelled her "a true artist"8 and the same year, in an advertisement for E Murray Fuller's gallery in Wellington, she was included in a list of "leading New Zealand artists" with such as John Weeks, D. K. Richmond and Francis McCracken.9

All the same she began to feel there was "something wanting"10 and when Mrs M. E. Tripe, a teacher at the Art Club, said: "We must have a clock," Scales interpreted the remark as an attempt to regiment the lessons and curtail her freedom to work. "It was like a knife being stuck into me,"11 she later said and the incident came to symbolise her feelings of separation from those for whom painting was a part-time activity requiring less than whole-hearted endeavour and commitment.

During the war the Scales family had suffered the deaths of their second and third sons, Arthur and Jack. Marjorie's husband, John Reeves, had also died when his ship, the S. V. Aurora, had gone down at sea in 1917. When George Scales, whose improprieties had for years humiliated his family, finally deserted his wife to marry his secretary, shame and social displacement were added to their already shocked and heartbroken state.

In 1919, in an effort to remake their lives, Flora, her mother and her sister, who now had her young daughter Patience to care for, went to Stoke, near Nelson, which they knew well from family holidays. There they built their house, Ikhona, and struggled to establish an apple orchard and strawberry plantation. Unfortunately, neither of the two young women were at all qualified for such a venture. Everything they needed to buy was extremely expensive or unobtainable due to the post-war depression and their naivety made them fair game for all those on whose help and advice their future success depended. As Scales's niece wrote:

“I can still see Aunt Lass pulling the hand plough and my mother steering and pushing it through the apples and strawberries and both being so exhausted. The strawberries they produced were beautiful but I don't think either the apples or strawberries gave them an income. Later, to help with finance Mother and Aunt worked in Kirkpatrick's canning factory when it opened up in the fruit season, canning everything, bugs and all, exactly as they were instructed.”12

This was a testing time for Flora Scales; her first real taste of independence from her father and experience of a life devoid of ease and luxury. She rose to the challenge and despite the combination of grief, anxiety and the grinding physical labour that consumed her days, made time to paint in the studio-cum-garden-shed they had built at the end of the garage. These paintings featured mainly animals and local country scenes such as Stoke, Nelson [BC013], in which the subject matter, rendered in broad bands of thickly applied sombre colour, can be distantly related to that of Charles-Francois Daubigny or Jean-Francois Millet from the Barbizon School.

Scales also gave lessons—two hours on a Saturday morning in her studio to the seven-year-old daughter of a neighbour who long remembered "Miss Scales's reserve" and being set to work at still life sketches of a "pile of pumpkins or a pair of old boots that lived in the shed."13—but the drive of her energy and pattern of living was saved for her own paintings. At the time, she was remembered by her niece as, "an isolationist, completely taken up by her paintings of the old worn out horses she bought to use as models."14

Undaunted by her distance from the main cities of New Zealand, Scales continued to send her paintings to exhibitions. Her work was seen in the New Zealand Academy of Fine Arts Exhibitions of 1922, 1923, and 1926. In 1925 she became a member of the short-lived National Art Association.15

With regular opportunities to exhibit, her works were invariably well received and a successful future in New Zealand seemed assured, but the feelings of dissatisfaction, so acutely experienced in Wellington, had not abated. She felt, as a follower of second-hand trends in style, as well as subject matter, that she was "getting nowhere" and had "outgrown New Zealand,"16 and, faced with what appeared to be a dead-end, looked elsewhere for ways to revitalise her own particular mode of expression.

It seems that Scales may have visited England from Nelson once or twice between 1924 and 1927 but the real opportunity for long-term change came in 1928 when her sister and mother decided to move to Christchurch for Patience's schooling. Scales saw that the time was right for her to make a life of her own and seized the chance, realising, as she was later to say, "I would never have learnt anything if I had stayed in New Zealand."17 Her family, understanding her pressing need to concentrate on painting, willingly assisted with her plans and later that year, when her father died in Wellington and her financial security was ensured with the small annuity of his bequest, she left New Zealand for England and Europe.

Scales went to Europe in search of knowledge and independence. As J. C. Beaglehole noted, provincial life is a limited society in which the "potentially mature individual has the unease, the discontent, the growing pains..." which bring about the decision to turn to the metropolis for contact with "more life...to be in contact with the heart of things, even if the heart of things is felt in poverty in a garret."18 There is an extensive list of women painters from New Zealand who made this decision, but most, eventually, returned home. Frances Hodgkins, who had left New Zealand twenty-seven years previously, only gradually loosened her ties with her family and home and for many years was torn between her wish to be with her mother in New Zealand and her knowledge that only in England or Europe could she live and work as a serious painter: "Art is like that—it absorbs your whole life and being. Few women can do it successfully. It requires enormous vitality..." she wrote in 1924.19

For Flora Scales, the "conflict between career and sentimentality"20 may have been less harrowing than for others. Since the thwarted romance of her youth she had grown as steely in her ambition as once her father had been on her behalf. Although she returned briefly to New Zealand in 1929, "feeling my way whether I was going to be a painter in France or an orchardist in New Zealand"21 the outcome was never seriously in doubt.

At forty-one years of age, a mature woman of backbone who "knew exactly what she wanted and where she was going,"22 she could plainly see that if she stayed in New Zealand she would be at the beck and call of anyone in need, and, no longer biddable, cut herself free to devote her life to art. To "wrestle" and to "hold on and hang on absolutely"23 became her motto and her creed.

Fig. 8: E. D. Kinzinger (1888-1963), Untitled, 1932, pencil and coloured pencil on paper, 170 x 134mm

Collection of Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand, Reference no. A-253-028

Reproduced with the kind permission of Nancy Kinzinger

https://natlib.govt.nz/records/22450056

Gifted to Flora Scales by E. D. Kinzinger in c.1933, Scales in conversation with B. de Lange, 1983, “when he said goodbye forever.” The drawing is inscribed, "To Miss F Scales, Edmund D Kinzinger."

Fig. 9: Flora Scales, Mediterranean Village [BC019], 1938

FRANCE 1928–1931

Flora Scales went by steamship to England where she met her cousin, Constance Hamersley, a keen amateur painter. Together they went on to France, briefly visiting Sydney Lough Thompson in Concarneau¹ and from there making their way gradually through the countryside to Paris.

Once in Paris, Scales rejoiced in her new independence, savouring to the full the life of a liberated, modern woman, free to wander at will, anonymous in the city streets:

“For the first ten days I just walked about the parks and Montparnasse thinking. I’d never had such a free time in my life...I rented a cheap bedroom in a little hotel nearby and had meals at a students’ restaurant.”²

Soon after her arrival she became friendly with a Russian émigré family, the Kalachnikoffs, through their four year old son, Boris, who she met playing in the street near his home. Bobby, as she called him, recalled their first meeting:

“On a sunny Spring morning in 1928 on the Boulevard Port Royal where we lived at number 88, Flora Scales and her friend met me in Montparnasse. Both were tall, slim and made radiant by beautiful smiles. A new way of life opened up for me. Flora Scales asked to see my parents. I ran quickly to look for my surprised mother. I insisted she meet Flora Scales. Thus a bond formed which began a friendship with a woman...completely straight, honest and totally guileless, where art was always present.”³

Flora Scales and Bobby became devoted companions, warmly affectionate and able to share delightedly in the events of each other’s life. She contributed to the cost of his education and they went on holiday together, to the South of France and, once or twice when he was older, to England.

While the final responsibility for Bobby always resided with his parents, Scales was able to take the role of an indulgent godmother and direct on to this appealing child, who felt misunderstood and unhappy at home, all the softness and gaiety she otherwise hid beneath a gravely reserved exterior.

Scales remained in touch with Boris all her life—his friendship and that of his family providing the security of a home in which she was always welcome⁴—but there was never a level of commitment or dedication in her relations with him, or anyone else, to equal the devotion she now addressed to her painting.

As a foreigner in France, without family or longstanding friends and with, at first, only a little of the language, Scales resorted to work with her paints and canvas as her main means of self-expression and self-respect.⁵ She became increasingly serious and intent upon her work. Her notes on Balzac’s image of the artist speak of the ideals to which she was drawn:

“What in art is praiseworthy is first of all courage, a courage of which the ordinary man has no conception...The artist belongs to his work. He must collect all his powers in it. The work can take rise only when it is conceived as the most important—as the only important sincere Matter of his being.”⁶

Scales’s courage and sincerity are born out in the epithet authentique⁷, used by Boris to describe his godmother as one who had thrown off all familial and social conditioning to become truly free and self-defining; more concerned to follow a self-determining path in her life and art than to accept a false position or fake a role to appease society.⁸

Scales often spoke of the sacrifices and discipline of her life as a student of art and compared herself to a ballet dancer—a particularly potent role model for an artist of that era when Diaghilev’s productions formed part of the vanguard in the revolution towards Modernism in art—whose whole life is dedicated to one goal, endlessly trying to reach a pinnacle of perfection. She said, “I too wanted to conduct an uninterrupted search for improvement in my work,”⁹ and in this spirit of asceticism deliberately adopted a spartan, solitary life, believing, “all artists are poor. If you have too many comforts you may slip into slovenliness.”¹⁰

These, the sentiments of a full-fledged romantic, were tempered in Scales’s case, by the precisely planned days and orderly habits of concentrated work and study that were the means to achieving her goals and gave her the credibility of a professional artist. She had learned from her father, the man of business, to scorn impracticality, sentimentality and enthusiasm.¹¹

Scales discovered many academies where she could work from the model, absorb the atmosphere and use the facilities offered to paint and draw. After sampling Colarossi’s, which she rejected as being “too dark,” she chose the nearby Acadèmie de la Grande Chaumière and in the following passage describes a day typical of those she spent there:

“In a big studio with about eighty men and women working. In the afternoon there were quick sketches from life for which you paid 6d. Poses lasted three quarters of an hour, then twenty minutes, then fifteen minutes; towards four o’clock, five minute poses when the model was getting tired. It was all students and smoke.”¹²

Although, as was then usual in an Acadèmie, little was offered in the way of formal tuition, sometimes she paid an interpreter to translate criticism of her work and she learnt, “one or two good things from a sculptor, a Monsieur Dana, who spoke English.”¹³

To augment this practical experience, Scales embarked on a programme of self-education in philosophy, art history and contemporary developments in art. She studied Balzac and made notes on his theory of Universal Unity, the interconnections and multiplicity of nature and the symbolism of numbers and geometric bodies. She and Boris visited art galleries together. He remembers discussions about the work of Matisse, Dufy, Bonnard and Seurat among others and has described their slow progress through the gallery rooms:

“She would stop for a long time in front of a painting, thinking and trying to find out how it was painted; concentrating and analysing...the qualities of two reds...”¹⁴

In the post-war 1920s Parisian museums were uncovering and exhibiting treasures from their vast collections of traditional art which, together with the profusion of contemporary and avant-garde painting to be seen, provided a wealth of study material for the eager art student.

Scales had quickly realised the valuable information to be gathered for her own work by studying that of other artists. A page from her notebook recording her tutor’s advice to: “Buy coloured prints of El Greco and study them...they will help you more than anything,”¹⁵ shows that she was following the current interest in this artist for the heightened expression his work was thought to gain by purely formal means.¹⁶ She collected postcard reproductions of the so-called Italian Primitives, Pisanello and Giotto, who were studied for their organisation of space. Artists such as Titian, Veronese, Tintoretto and Vermeer, valued for their knowledge of colour harmonies, also came under her close scrutiny.

Scales seized upon the right to examine, study and absorb the knowledge so acquired until it emerged, transformed, as something of her own making. She said: “How would I be painting if I’d never seen other work—would I be doing the bullocks in the caves in Lascaux? Everyone who looks is influenced by other things.”¹⁷ At the same time she constantly and emphatically affirmed the importance of artistic authenticity or genuineness and had no wish to imitate the style of any particular school or teacher. As she explained: “The thing is to forget you’ve been influenced. I didn’t want to be like anybody. I wanted to be a little uncommon, unusual.”¹⁸

A landscape from Scales’s early visits to the South of France between 1928 and 1931, Untitled [Pink Tree, Village and Bay] [Fig. 4], with its elevated viewpoint and flattened, geometrically simplified planes of bright, unmodulated colour, shows her moving towards non-representational methods in her employment of colour and form.

This painting and another from the same period, Untitled [Two Green Trees] [Fig. 5], are related by subject and one of these two works may have been that which Scales sent, under the title of St Tropez, to the Autumn Exhibition of the New Zealand Academy of Fine Arts held in June 1932.¹⁹

The exhibited painting (New Zealand Academy of Fine Arts Autumn Exhibition Catalogue No. 101) was one of a group, including works by John Hutton, Leslie Greener and Christopher Perkins, which was hung at the “centre of interest...above the dais,” and categorised as, “examples of modern or even ultra-modern art.”²⁰ Reviews of Scales’s painting describe it as “a lively, unconventional landscape [which] upon close study reveals a harmony of colour and arrangement, no doubt the outcome of much searching and sincerity,”²¹ and as “an extraordinary kaleidoscopic effect...with splashes of colour,”²² referring to the influence of Post-Impressionism on her work in the first few years after her arrival in France.

Despite the impression of warmth and brightness emanating from her paintings of this period, so markedly in contrast to the subdued, pensive mood of her earlier Nelson paintings, Scales was “worried and wanting to get on”²³ with the search for information that would provide the key to her own development.

The abundance of paintings from every period in Paris caused her later to remark: “In Paris you can’t learn anything—the Germans are the teachers—but you have everything for study in Paris.”²⁴ Which suggests that she had not, so far, met a suitably inspirational guide or teacher.

In the Parisian academies of the 1930s, such as that of André Lhotè, Cubism was explained in scientific terms as part of the current effort to rationalise and order the artistic process, “irrespective,” as art historian Sheldon Cheney has pointed out, “of the newly understood tensions and volumes in space, or the dynamic properties of colour.”²⁵ This stagnancy and the irrelevance to her of the utilitarian art then in favour in France contributed to her feelings of restlessness and disenchantment.

At forty-four years of age she felt she no longer had the time to waste on “old fashioned schools you could find in your own back-yard.”²⁶

When she went to St Tropez for the summer of 1931 she was already in search of fresh new directions and stimulation. She said: “You don’t want to have a meal of all the same things all the time...I wanted variety, not bread and butter, bread and butter, bread and butter,”²⁷ as if she felt herself at a stalemate similar to that she had experienced prior to leaving New Zealand in 1928.

-a-1645236923.jpg?ixlib=js-3.8.0&auto=format&w=300)

Fig. 10: Flora Scales, Basilica and Lighthouse, St Tropez, Southern France [BC021], 1939

Fig. 11: Flora Scales, Greniar [Graniers], St Tropez, Southern France [BC024], 1939

STUDY IN MUNICH

In the summer of 1931 Scales met Frances Hodgkins and her companion, Gwen Knight, in St Tropez where they “sat and talked under six big elms in the park.”¹ Sympathising with Scales’s predicament and her apprehension over her future as an artist, Gwen Knight suggested she move, in her capacity as an art student, from France to Germany. Germany, widely acknowledged as the breeding ground for all that was most modern in art during the 1920s and up to 1933, was also the home of Hans Hofmann’s School of Fine Arts in Munich, at that time one of only four European art schools teaching the principles of Modernism.²

Hofmann was familiar to many of the artists who gathered annually in St Tropez from the summer schools he had conducted there with his translator, Glenn Wessels, in 1927 and 1928.³ Two American students, Ruth and Helen Hoffman, who attended one of these schools, describe in their book, We Lead a Double Life, the effect of first meeting his radical and seemingly outlandish ideas:

“It was like nothing we had been taught before. We were nonplussed when we were told that a mountain, though it was far away and seemed small, could be painted larger than a house that was close, because it actually was larger than the house...He had a theory all his own about line, rhythm, tension and composition. It was sometimes quite incomprehensible to us.”⁴

Hofmann’s art education had begun in Munich where, as a young man, he had studied the Old Masters in the collections of the Alte Pinakothek. In the city galleries in the late 1890s he had also been introduced to the work of the Seccessionists, the Impressionists and the Post-Impressionists.

In 1904, at the age of twenty-four, Hofmann went to Paris where, for ten years, he worked in close proximity to Picasso, Matisse, Braque, Gris, Roualt and Delaunay, the direct beneficiaries of Cézanne’s revolutionary vision and the spatial counterpoint he achieved on his canvas.

From his years of accumulated study and experience, by 1918 Hofmann was evolving an analytical overview of art, fully cognisant of, yet original in its interpretation of tradition, on which to base his teaching.

Primarily, he proclaimed the autonomy of the art object. Like Cézanne he outlawed systems of single point perspective and, out of his knowledge of the German Romantic tradition, the colour theories of the Fauves and the aesthetic philosophies of Kandinsky and the artists of the Blaue Reiter group, he built a compelling argument for the abstract, expressive power of colour and form; the “inner laws” of the artists’ materials which he felt had been his “greatest discovery.”⁵

Hofmann’s reputation as an eminent teacher was based on his ability to unerringly select from the many strands of Modernism and traditional art which he had studied, the material he needed for a theory of pictorial or autonomous painting which, “applied to all art.”⁶ His students understood that whether their work was abstract or based on visual experience mattered less than the plastic or purely pictorial means they chose for its achievement.

He was also renowned for the exceptional degree of freedom and artistic independence he encouraged in his classes. As an art reviewer, writing retrospectively in 1983, noted:

“[Hofmann was] remarkably responsive and fluid as a teacher...[able to] recognise originality in widely varying forms...[and] to perceive the needs and talents of each pupil. This openness, in turn, prompted a spirit of artistic experimentation, optimism and freedom.”⁷

Acutely protective of her treasured independence, Scales sought above all in a teacher one who would respect the authentique quality of her artistic life and equip her with the tools to realise her full potential. It was with some perception that Gwen Knight had divined the suitability of the Hofmann method for her new friend.

Inspired by Knight’s enthusiasm, ever-hungry for experience and perhaps bolstered by the memory of Mina Arndt’s fruitful years in Germany, Scales set out for Munich in the winter of 1931, accompanied by her cousin, Connie.⁸ On arrival she found Hofmann in the midst of preparations for emigration to America, having incurred the censure of the Nazi authorities as a Jew and a propounder of degenerate art theories. Frau Hofmann, who she described as, “very German with a clear skin and round face and hair cut with a severe fringe. Very approachable and likeable,” invited her and another student, “a rich American lady,” to tea. The occasion was remembered by Scales with some amusement:

“We were directed to the house by a quiet way. To enter we had to open a white wooden gate by lifting a simple latch. The American lady was shocked at being told to come by the back door, but it appealed to me. We had sandwiches for tea.”9

Scales also remembered the biting cold of the Munich winter and the shock of seeing jack-booted, brown-shirted soldiers in the streets. With hindsight it may well be surmised that the instructions to arrive at the house “by a quiet way” were precautionary, to avoid drawing the attention of the menacing military or civil police to the household or their guests.

Naturally enough, given Hofmann’s situation, the school was impoverished and winding down and Scales’s tuition, as one of the few remaining students, was left in the hands of his English-speaking, Lutheran assistant, Edmund Kinzinger.¹⁰ Under his supervision the zeal and productivity of Hofmann’s classes was faithfully maintained and Scales found the combination of disciplined purpose and liberty of means that art critic Harold Rosenberg has called the “ultimate principle of the school,”¹¹ a welcome contrast to the laissez-faire attitude of the French academies she had so far experienced.

The surviving sketchbooks and notes from Scales’s nine months at the Hofmann School¹² as well as the records of her later conversations on the subject, illustrate just what Kinzinger provided her with as the principles of Modernism.

Informed by contemporary studies into the physiology of human eyesight and the perception of space and in keeping with current discourse on the role of art and the artist in society, Kinzinger brought to his lessons, as Hofmann had, the concept of a painting as a self-contained entity, an autonomous object with its own laws of construction and dynamics governed solely by the materials of painting and the imagination of the artist, also deemed autonomous.

He demonstrated as “distortions of perspective,”¹³ those rules of art and architecture which since the Renaissance had dominated the compositions of Western artists, and Scales, like the Hoffman sisters in St Tropez, came to see that, “the jars are just the same size a long way off as they are close to you...We made up our minds to do away with perspective,”¹⁴ and disengaged her work from what the Modernists, since Cézanne, thought of as externally imposed and conventional rules in favour of those dictated purely by internal pictorial necessity.

A theory attributable to Klee’s pedagogical writings: “A point moves and we get a line. A line makes a plane and a plane makes a volume and if a volume moves it makes a movement,”¹⁵ was used as a starting point for the studies in structure and dynamic, organic movement with which Scales was to discover ways to suggest space and volume without resorting to the illusionism of linear perspective. [Fig. 6-7]

Further to this, she was encouraged to explore the effects of tilting and turning the axis of an object from the horizontal and vertical edges of the canvas and of manipulating the outlines of overlapping planes. She analysed the resulting imbalance and asymmetry and the effects of dissolving outlines to determine how such techniques could be used to create an autonomous pictorial space.

Above all Scales learned to construct space in her painting by orchestrating the tensions and relationships between plane, volume, colour and texture into a rhythmic, unified whole according to Hofmann’s theory of push and pull, “in which depth responds to the picture plane and vice versa,”¹⁶ the forces and counterforces by which a construction was to be given “a life of its own ... a spiritual life,”¹⁷ and by which the expressionistic power of the medium could be fully explored.

Scales’s meeting with Kinzinger marked a turning point in her life and the beginning of her “real paintings.”¹⁸ It was a fortuitous encounter coming when she was most in need of, and receptive to, a well formulated, clearly articulated course of teaching. Unlike the Hoffman sisters, she was neither nonplussed nor uncomprehending. The technical and intellectual education she had worked at with such concentration in France, predisposed her towards the comprehensive philosophy of the act of painting Kinzinger put before her. It corresponded with her need for independence and love of self-discipline and was to be fundamental to her creative processes for the rest of her life.

Scales’s studies with Kinzinger continued in St Tropez over the summer of 1932. A page from her notebook dated 17 June [1932] records his tutorial on the use of multiple viewpoints to convey movement and space in the composition [BC112 pg 13]. As she explained: “Kinzinger gave me new ideas. For instance, to have direction [in my painting]. This was new to me, to see one thing behind another. To see things from one side of the canvas and then go to the other side and see it from another point of view.”¹⁹

The coloured pencil drawing Kinzinger gave Scales when “he said goodbye forever,”²⁰ illustrates the points he was teaching [Fig. 8]. It also, with its jauntiness and wit, refers to the hedonism and ease of life in the South of France and provides a telling contrast to the menacing atmosphere of 1930s Munich which lay behind them.

Fig. 12: Flora Scales, Port of Weymouth Bay [BC025], 1945

Fig. 13: Flora Scales, St Michael [BC041], c.1958-1962

RETURN TO NEW ZEALAND, 1934–35

Scales returned to New Zealand in 1934 to spend a year with her mother in Nelson while her sister and niece went to England.

Early that winter, Toss Woollaston, whose curiosity had been roused by Scales's paintings at her sister's house in Christchurch, called on her to ask for lessons. Avid for knowledge and in a frame of mind similar to Scales’s in France three years earlier, he had discovered in her paintings, “something more disciplined than mere attractiveness [which] made me want to understand what that something was.”¹

What Woollaston found, when he went to introduce himself, was a “shy, middle-aged spinster”2 who was wary of teaching and reluctant to give up her own closely-guarded painting time. As it eventuated, he had five sessions of conversation and practical work with Scales, who, as a continuing link in the chain of those disseminating Modernist theory, imparted to him the essentials of Hofmann’s doctrine.

Until Scales's return, artists in New Zealand had largely relied on the art teachers from England, W. H. Allen, R. N. Field and Christopher Perkins, for informed discussion of contemporary art theory. Their studies, however, did not encompass the implications for space, volume and movement, contained in the concept of plastic, or pictorial, composition, which was central to the lessons of Hofmann. Woollaston, who instinctively felt there was “something more” than his teachers had so far offered, and, equally intuitively, recognised Flora Scales as its source, opened the way for the theory of European Modernism to be introduced to New Zealand. He also, by his habit of relaying her lessons to his friend, the artist Rodney Kennedy, in Dunedin, became a link in the Modernist teaching chain himself and so expanded the range of Scales’s considerable contribution to New Zealand art history.

“Going today for a seance with Miss Scales,” he wrote, “I am being spirited out of my dependence on perspective and some other vices.”³ As he went on to explain, he was learning that, “the created three-dimensionality [which] does not destroy the essential two dimensionality of the...picture plane...is created by movement and tension relations of the form and the colour and not by obvious imitation of material or obvious three-dimensional things.”⁴

Scales counselled Woollaston to work from a position above and to one side of his subject in the landscape to circumscribe distance and cause objects within it to appear as overlapping planes, in his search for a structure independent of linear and aerial perspective. She showed him too, that by concentrating on the tensions between planes set parallel to the two dimensions of the canvas and those at an angle to its vertical and horizontal edges, he could create an impression of dynamic pictorial depth.⁵

He was instructed to observe that, “lines diverging outward correspond to our sense of space increasing as you get further away,”⁶ and, as she demonstrated in the course of their discussions:

“Distance is not attempted by diminishing the size of objects or the force of colours…If you have a house and a mountain as picture parts in the same picture, you give them the sizes they require to function pictorially, arriving at these through studying the space-relations, not through half-believing an academic formula.”⁷

Included in Woollaston's letters to Kennedy is his excited description of Scales’s use of colour which was to be a major influence on his own painting:

“I am agog. She has Tasman Bay and red mountains jumping on the blue sea—but it is so obviously necessary that they should, there are such orange-red and magenta roofs on the Tahunanui hillside in the foreground…reds in the hills across the water as if the distance had come close up and yet was still distant. On instructed reflection it corresponded to the nature of the painting, actually on a flat surface, no part physically further from us than another.”⁸

Flora Scales warned Woollaston that the information she had given him required his long and thoughtful consideration and that he “must not expect to understand in a day, a month or even a year.”⁹ Her own painstaking methods of work, far removed from the spontaneity of her earlier plein air paintings, are reflected in her injunction to:

“Draw for a month, then, when you can find out no more about the subject, pin a butter paper over it and paint on that, then, if the painting is good, transfer it to the canvas.”¹⁰

Scales also insisted that her lessons were not hard and fast rules to be blindly followed but guides for future study and artistic development. She knew, as Woollaston noted in his December letter to Rodney Kennedy, that “Hofmann will theorise and always cap it off with, ‘but in the end it is only by one’s feelings one can create a piece of art’.”¹¹

After a short while Scales made it clear she did not wish the meetings to continue and retired to her secluded life. Conscious as always of her imperative need to use her time for painting, she did her best to avoid extraneous demands. In a contemporary letter, Woollaston gives a revealing account of her completely unselfconscious preoccupation with art:

“She takes infinite pains and is very humble about her work...says she is only a student…She is sweet and kind and dignified and utterly removed from both sophistication and frivolity…She conserves her time and energies as much as possible for study. Her attitude seems to be that to draw and paint is better than to discuss drawing and painting. She is not ‘arty,’ not being afraid of being arty.”¹²

Woollaston had found Scales detached and self-possessed, wanting only to work without distraction. But there is evidence to suggest that, while in New Zealand, she was far from as secure and self-sufficient as she outwardly appeared.

In an episode closely mirroring her meeting with Bobby in Paris, she had befriended, and yearned to adopt, a little four year old boy, met at the beach near Nelson. Her hopes, unrealistic and impracticable as they were, could not succeed but subsequently she and the child’s family established a warm friendship, their affection, like that of the Kalachnikoffs, happily filling a gap in her emotional life and providing a buffer against loneliness during her visit to New Zealand.¹³

Since his lessons had ended, Woollaston had looked for a chance to study more of Scales’s work. His proposal to the Committee that she be Guest Exhibitor at the 1934 Spring Exhibition of the Suter Art Society was acted upon and he went “every day” to look at her paintings in which the “colours glowed from deep space…and the dark, rubbed drawings extended deep into their own grey surfaces by virtue of lines that had been worked for a whole month.”¹⁴

The art critic of the Nelson Evening Mail had some feeling for Scales's aims and described her work as:

“Bold in design and generally rich in colour and sunlight. These pictures illustrate a complete breakaway from the older accepted traditions and a venturing into realms where emotional representation rather than literal transcription is a dominant motive.”¹⁵

However, not everyone who visited the exhibition was won over as Woollaston's letter reveals:

“Miss Scales has eight works in the present exhibition. [W. H.] Allen appreciates the created or spiritual third dimension in them but people who depend for their conception of three-dimensionality upon the theory of vanishing perspective which has to do with optical mechanics and not the inner conception, can’t see it at all.”¹⁶

Indeed, in some quarters the paintings were greeted with an “uproar of criticism”¹⁷ that was as much due to the still evident butter paper and drawing pins Scales had seen fit to include, as to their “so-called ‘modern’ [style].”¹⁸

Balancing the outrage were the opinions of those who, like Woollaston and Allen,¹⁹ had found their interest and curiosity engaged by Scales’s work. Roland Hipkins viewed her paintings at the 1934 Annual Exhibition of the New Zealand Academy of Fine Arts.²⁰ Pointed out as, “the most provocative in the exhibition,” they were prominently hung with other “samples of ‘modern’ art” by artists such as Sydney Thompson, Lois White, Roland Hipkins and W. H. Allen.²¹ Hipkins’s review of the exhibition for Art in New Zealand contained a thoughtful analysis of her work:

“The paintings of Flora Scales strike a note not common to a New Zealand exhibition. She prefers not to bind herself to accepted principles of perspective and naturalistic representation. Her aim is to create a theme based on abstract orchestration of line, mass and colour. Within these limits she presents compositions which are stimulating and of unusual interest.”²²

Frederick Page, who had, since the 1920s, kept abreast of the European artistic avant-garde, wrote a more outspoken defence of the paintings she exhibited with the New Zealand Society of Artists the same year:

“None of the modernist group…amounted to very much, excepting the pictures of Flora Scales. Powerful, even repellent, they had a genuine look which the others completely lacked; they also had much in common with those reproductions one sees in German tomes on modern art labelled, “Expressionismus und die Gegenwert” … even to the guitar.”²³

The reviews make it clear that Scales’s paintings stood apart from those of other artists exhibiting in New Zealand, including those who had studied overseas. Behind the distinctness lay the philosophical and practical principles of art to which she tenaciously adhered.

Foremost of these was Scales’s belief that the activity of painting was a vocation requiring her complete devotion and dedication. She was enthralled, captivated and spurred on by the process of her art through which she found and expressed her independence and her reason for living—put simply, she lived and loved to paint. As Boris Kalachnikoff was to write: “Painting was her refuge, her passion, her reason—her intelligence.”²⁴ Underpinning and validating this passion was the considerable body of learning she had amassed which gave her enquiries into the nature of pictorialism the authority and integrity of a genuinely professional artist.

Next to this stood Scales’s equally passionate belief that a work of art took form and existed without reference to external influences. Although the 1920s and 1930s saw the advent of many changes in New Zealand art, the idea that paintings could express an innate, autonomous vitality through relationships and volumes of colour and form, had not yet gained full currency and many artists sought to organise their compositions according to a pre-conceived geometric design. As a critic wrote of Olivia Spencer Bower’s work in 1932: “The artist sees nature in pattern and boldly eliminates detail for effect.”²⁵ Furthermore, many of these idealised, well-ordered images were used to serve an emerging New Zealand nationalism. The idea of burdening her work with either pattern or politics was an anathema to Scales who, with Hofmann, believed that: “The artist’s real problem is pictorial—neither distortion, representation, history, allegory or symbolism is art.”²⁶

Discussing her Mediterranean landscapes from the 1930s Scales declared, “It is as the place is. I follow Nature.”²⁷ But her landscapes are neither mimetic nor schematic. To follow Nature she worked towards a pictorial expression of her subject by “searching for the reality of the image on the canvas, through working the paint,”²⁸ endeavouring, as Hofmann was to say, “to interpret visual experience into plastic experience.”²⁹

The words of Gordon H. Brown on Modernism in New Zealand in the late 1940s and early 1950s accurately describe Scales’s work in New Zealand ten years earlier when she was already painting:

“Not from the outside, as it were, where the subject of the painting dominates, but from the inside where the formal elements of art give to the subject a context that recognises a painting as being primarily the product of the medium of art.”³⁰

To art gallery visitors in 1934, Scales’s work may well have appeared raw and roughly-hewn, fully justifying Page’s view of it as: “Powerful, even repellent.” But, unshaken by public opinion—after all, as she remarked, “who knew enough to comment,”³¹—she persisted with her study and investigations, totally committed to following the path she had chosen for herself.

Fig. 14: Flora Scales, Untitled [Mousehole Cornwall 3] [BC030], 1950-1951

Fig. 15: Flora Scales, Seated Woman, Warwick School of Art, London [BC036], 1959-1961

FRANCE AND ENGLAND, 1936-1972

After her return to Paris early in 1936, Scales attended classes at the Acadèmie Ranson given by the influential teacher, Roger Bissière. Bissière, who had been described by Clive Bell as the Romantic antithesis of Andre Lhotè,1 is recorded as saying:

“I used to persuade any pupils that really interested me to leave the Acadèmie since I felt that the only effect it would have on them would be to get them into disastrous habits.”2

As with Hofmann and Kinzinger,3 Bissière's respect for his students' individuality and his Modernist beliefs provided the inspiring intellectual context Scales sought for her work.

Among her papers [BC112, pg 5] are notes from Bissière's lectures including refinement of form and colour and the selection of compositional elements towards a greater intensity of expression in painting. The lecture notes also echo Hofmann with a description of the artist as sole arbiter of the work, seeking to express a personally conceived inner vision, informed by, but unimpeded by, tradition or teachings. Once the artist had acquired the necessary basic discipline and technique, he said: "You will be able to forget these instructions and rely only on yourself; in other words on your own sensibility, as finally it is the heart that justifies everything and I can no longer be of help to you."4

In later years Scales spoke with admiration and affection of both Kinzinger and Bissière whose ideas about painting rang true to her instincts and with whom she felt a sense of common purpose.5 However, while acknowledging the value of their influence, she emphasised that she had never tried to imitate their work but used the information they imparted as stepping stones towards her goal. She said, "I took advantage of their brains pushing me on. I made use of them as a step up the ladder,"6 perhaps unconsciously drawing on the image of her ambitious father's crest depicting a ladder against a wall, to describe her artistic self-development.

While she regarded herself as a student of art for the rest of her life, Scales took heed of Bissière's advice to put her faith in her own judgement. Now the lessons arose out of her own series of paintings which provided new challenges and the chance to resolve problems in many different ways. As Bissière had said: "Do not try to do a painting to be 'successful'; this has no point. On the contrary, try to learn something and to improve your knowledge."7 To which Scales added: "You have to create and develop every day. In the learning of three things you may suddenly find a fourth."8

As far as is known to date, Scales's work of the 1930s came to an end with two main groups of paintings from the South of France [Fig. 9-11]. In each group she has studied a particular landscape from various viewpoints and experimented with shifts of colour and volumetric proportions to bring about subtle changes in her expressive construction of space [BC019, BC020, BC021 form one group; BC023, BC024 the other].

These paintings, whose value to Scales is reflected in the fact that, of the five, two were sent to New Zealand as gifts for her niece and three remained in her possession until the 1970s, show her working steadily towards a pictorial analogy of the landscape. Unfortunately, just as this point of confidence and clarity of vision was reached, Scales's life as a painter was suspended by world and family events until the late 1940s; a gap of nearly ten years.

In June 1940 Scales arrived in Paris from the South a matter of days before the occupying forces of the German Army.9 As the holder of a British passport, she was at first required to register daily with the Commissioner of Police, but in December she was interned and taken by train with other British and American women to barracks in Besançon. Recently vacated by a unit of the French Army, these premises proved unsuitable for civilians and in May 1941 they were moved to Vittel, near the Vosges Mountains in the north-east of France, where Scales remained until October 1942.10

After a period of serious illness requiring hospital treatment, she apparently adapted to life in the camp with relative equanimity. Perhaps, in its communal and regulated style, it was not too dissimilar to her life at the Taumaru Military Hospital. She took pleasure in the beautiful grounds surrounding what had once been a spa resort and seized every chance to sketch when she could, accepting the respite from the self-imposed strictures of her life as a free citizen.

When she was returned to Paris to fend for herself in ill health, Scales's situation became more difficult. She suffered from shortage of food and the intense winter cold and resorted to art classes in order to survive, having found out that heating was supplied where there were German students. Her misery was compounded by the discovery that the English-run warehouse in which she had stored her paintings had been ransacked and all was lost. Nothing of the work, amongst which were, "hundreds of nudes from Paris and Munich"11 has ever been located.

Following the liberation of Paris, Scales was one of the first to be airlifted out to England by the American Air Force. She arrived in much-mended black peasant clothes carrying her last Red Cross issue of potatoes and salt for her family, believing, as the propaganda had it, that their deprivation had been greater than hers.12

Scales's mother and sister had lived in Surrey during the war but, in 1946, when ships once more became available for civilian transport, Marjorie and her second husband left England to accompany their grandchildren to New Zealand.

Scales remained in England with her mother. They shared a flat in the village of Eversley near Camberley, and, as evidenced by the drawing Preston Church [BC102] and the painting Port of Weymouth Bay [Fig. 12] took short holidays and excursions together as far as the basic petrol allowance of ninety miles a month allowed. But the "exacting life of looking after her mother for so long"13 took its toll on her and the conflict between her "feeling of great delight at being able to be with Mother"14 and her longing for lost independence brought her close to the point of despair where she "nearly gave up painting."15 As a concerned friend reported to Marjorie Hamersley in New Zealand, mentally and physically the responsibility was proving to be more than her sister could manage.16

In April 1948 when Gertrude Scales became seriously ill with bronchitis, family members, not realising how ill-equipped Flora was to deal with problems or personal relationships after her debilitating war-time experiences, were hurt and bewildered by what looked like implacable coldness and her "difficult, stone wall nature."17 She would not countenance, while her mother was still so weak, Gertrude's longing to return to New Zealand and her letters to Marjorie, who had thought the travel plans watertight, became increasingly curt and abrupt. Finally, after Gertrude's death, Scales no longer replied to Marjorie's letters at all and a rift developed out of the misunderstanding that was no doubt painful to both sisters.

Scales was sixty-one when her mother died. With remarkable resilience and with her determination once more resolved she resumed her work. For the next twenty-four years she lived as a travelling artist in London, Cornwall, Paris, or the South of France taking lodgings or staying with the ever affectionate Boris and his wife Christiane.

In the early 1950s Scales went to Cornwall where it was still possible to live economically. She spent some time in Mousehole and Penzance but was chiefly attracted to the old fishing port of St Ives which had been home to colonies of artists since Whistler stayed there in 1883.

The recollections of her great niece show that Scales held fast to her opinion that excessive comfort brought with it the threat of sloth:

“I visited her there in a sparsely furnished house on the side of a hill. It was jolly cold and the wind was prevented from making life completely miserable only by thick red velvet curtains. Heavy as they were they still blew at an angle into the room...I was appalled by the lack of comfort with which she lived her life.”18

St Ives was then the hub of artistic activity in the South of England and Scales recalled passing Barbara Hepworth's Trewyn Studio and hearing the sculptor at work but, modest and considerate as ever, "didn't like to disturb her and never went in."19 Other artists in residence whose works were in the forefront of international modernism were Patrick Heron, Victor Pasmore, Terry Frost and Roger Hilton.

To date there is no evidence that Scales participated in the numerous local or touring exhibitions organised by the highly motivated artists in Cornwall. Probably she lived quietly and studiously, as in France, setting herself apart from others who were, in the main, considerably younger.

Fig. 16: Flora Scales, Boarding House, St Ives, Cornwall [1] [BC060], 1968 -1970

Fig. 17: Flora Scales, From Beach Road, St Ives, Cornwall [BC064], 1969

Notwithstanding her solitary life, Scales's development followed the path taken by the most spirited and advanced international groups including the French Abstract Impressionists such as Bissière, and the Abstract Expressionists in America, who were themselves influenced by Hofmann, Patrick Heron and Roger Hilton. In doing so she by-passed geometric abstraction and the post-war Romanticism of such as John Piper and Graham Sutherland, to fully explore, in those works revealing a greater degree of abstraction, for example St Michael [Fig. 13], the dynamic and structural properties of colour.

Patrick Heron, writing in 1955, called colour "the vibrant generator of space"20 and Scales, in conversation nearly thirty years later, recalled consciously drawing on the theories of autonomous spatial colour she had studied with Kinzinger and her deliberate turn to colour for spatial vitality in her painting. "I arranged with myself not to see too many planes—only colour," she stated.21

Although her ideas corresponded with those of other colourists, including Hofmann in his practice of "forming with colour,"22 in effect, possessed by the courageous perversity that disallows acceptance of ready-made style, her search for expressive solutions resulted in paintings that are uniquely her own. Whereas, for instance, Patrick Heron's colour in the 1950s was often saturated, brilliant and vigorously contrapuntal, Scales employed a narrow range of low key colours in her carefully worked out constructions. Using watery, smudged and muted colour she explored close-knit harmonies of proportion, tone, transparency and contrast to produce apparently tranquil paintings such as Untitled [Mousehole, Cornwall 2] [BC029].

In 1953 Patrick Heron wrote of the balancing act required for the creation of pictorial space:

"On the one hand there is the illusion indeed the sensation, of depth; and on the other there is the physical reality of the flat picture-surface. Good painting creates an experience which contains both. It creates a sensation of voluminous spatial reality which is so intimately bound up with the flatness of the design at the surface that it may be said to exist only in terms of such pictorial flatness. The true and proper care of the painted surface of the canvas not only fashions that canvas well—as an object in its own right—but also destroys it."23

That Scales already understood these dual concerns is demonstrated in the characteristically controlled composition of Untitled [Mousehole, Cornwall 3] [Fig. 14]. Here, against the hazy, flattened forms that make up the images of the harbour, the dark diverging lines of the derrick image restate the two-dimensional surface of the canvas. They also suggest the possibility of increasing the viewer's awareness of the spatial reality so created in the picture. The delicately maintained balance between the sensation of depth and the flat picture surface respects both aspects of the painting identified by Patrick Heron.

From October 1959 to July 1960, Scales attended the Heatherley School of Fine Art in Warwick Square, London.24 The School was run as an atelier or studio and one of its draw cards was that, "drawing from the nude model [was] constantly available to anyone who could pay the relatively low fees."25 No doubt Scales took full advantage of this opportunity but it seems that all her life studies have since been lost or destroyed.